20/3/2020 Greater Prairie-ChickensWhen I was invited to speak at the North American Bluebird Society conference in Kearney, Nebraska, last week, we were lucky to have a generous friend arrange to take us out to see a Greater Prairie-Chicken lek. Prairie Chickens have been on my bucket list for many years.

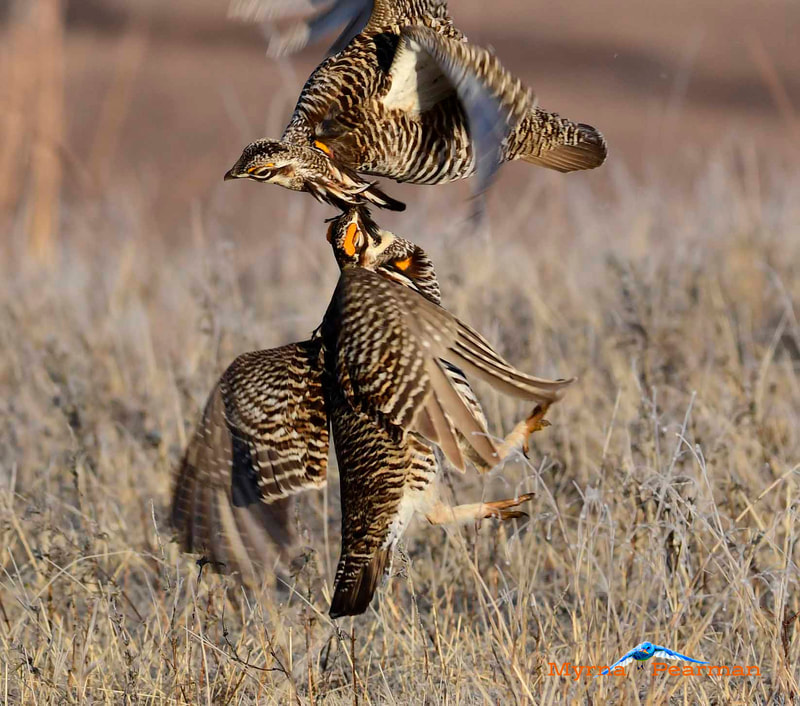

Greater Prairie-Chickens once inhabited the sweeping grasslands of North America, including the prairie regions of Alberta and Saskatchewan. However, their range has been greatly reduced, thanks to habitat loss, hunting and competition from the introduced Ring-necked Pheasant. They are now found only in a few American states. We arrived at the lek, located on a small hilltop in a large native pasture, just before dawn. We sat quietly in the inky cold, awaiting the arrival of the males. We were first alerted that the show was about to begin by a sound - the ethereal cooing call of the first arriving male. He was joined by another dozen or so other males and we were soon surrounded by mournful-sounding balladeers. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Greater_Prairie-Chicken/sounds The birds materialized as the darkness slowly faded and we were, for the next couple of hours, treated to an amazing sight. Our guide explained that the females would not likely put in an appearance for another couple of weeks, so it was a treat to have one show up, just before the sun's first rays kissed the hill. Her presence threw the males into paroxysms of dance but she, apparently finding no suitors to her liking, soon scurried away over the far hill. As the sun came up on this perfect Nebraska spring morning, we enjoyed a spectacle of colour, activity and sound. I was quite amazed at how different their dance moves are from Sharp-tailed Grouse (which are still found, albeit in declining numbers, in Alberta) and it was apparent that these birds inspired the famed Indigenous chicken dances. Like all lek species, male Prairie-Chickens defend a small territory on the dancing ground. To demonstrate their prowess, they extend their orange eye combs, lower their heads, raise their neck feather tufts (called pinnae) to reveal bright orange air sacs that create a booming sound, stamp their feet, click their tails and shake their wings. They divide their time between looking around and fighting with each other. Their sparring alternates between stand offs, chasing each other and - on occasion - leaping into the air to do battle with wings, feet and bills, They also perform flutter jumps, leaping into the air while flapping their wings and issuing loud vocalizations. It was a challenge to photograph them performing these spontaneous jumps! Our guide advised us that it is usually only one male that mates with all the visiting females - he with the most experience, the most impressive eye combs, longest legs, and best territories (nearest the center of the lek). As with all grouse species, no pair bond is formed and the males play no further role with the family. We left the blind - hearts filled with joy - after the warm morning sun melted the frost and the males had wandered off to feed for the day. What a privilege it was to bear witness to this marvel of nature. |

AuthorMyrna Pearman Archives

August 2022

|

|||||||||

All photos and published works on this website are copyright Myrna Pearman unless otherwise noted.

Re-posting these images or publishing is not permitted without Myrna's written consent.

Copyright Myrna Pearman Publishing 2024- Site design and maintenance by Carolyn Sandstrom

Re-posting these images or publishing is not permitted without Myrna's written consent.

Copyright Myrna Pearman Publishing 2024- Site design and maintenance by Carolyn Sandstrom

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

31/3/2020

0 Comments