Red Deer Advocate- 2019

December 2019: Evening Grosbeaks

It is very likely that Ellis Bird Farm (EBF) owes its existence as much to Evening Grosbeaks as it does to Mountain Bluebirds. Long before Charlie and Winnie Ellis were caring for the bluebirds, they attracted backyard birds to their farm by NatureScaping their yard and establishing a large bird feeding program. Each winter, Charlie would shovel about two tons of sunflower seeds (one year he went through 11 tons) onto cattle troughs for the massive flocks of Evening Grosbeaks that descended to feed. The Ellises loved their winter birds as much as they did their summer ones.

When I started at EBF in 1987, Charlie and Winnie were still feeding grosbeaks. During the winter of 1990-1991, while writing my first book (Winter Bird Feeding: An Alberta Guide), I enjoyed watching the Evening Grosbeaks at the feeders outside my office window. Alas, over the next few years they seemed to disappear. Even though the species is considered to be an irruptive migrant (absent one year, then abundant the next), their decline was widely reported across North America.

The story of Evening Grosbeak population dynamics is both interesting and puzzling. Rarely seen east of the Rockies before the mid-1800s, they then began moving eastward with each winter migration, reaching the east coast in the winter of 1910–1911. Their rapid expansion may have been facilitated by a new, abundant and secure winter food source—ornamental Box Elder shrubs that were widely planted in rural yards and urban subdivisions.

Thanks to citizen science initiatives such as Christmas Bird Counts and Project FeederWatch, anecdotal observations of population losses were backed up by data that confirmed both declines and range contractions: between 1988 and 2006, the number of FeederWatch sites reporting Evening Grosbeaks declined by 50%; at stations that continued to report them, numbers declined by 27%.

Many factors have been implicated in the decline, including climate change, large-scale forestry operations that remove the diverse old growth forests upon which they depend for nesting (in one study, no Evening Grosbeaks were found nesting in forests that were less than 100 years old), other habitat destruction and the aerial spraying for spruce budworm.

The birds are also prone to diseases, including a bacterium (Mycoplasma gallisepticum) as well as salmonellosis and West Nile virus. As if these afflictions aren’t enough, Evening Grobeaks are also susceptible to the parasitic infection by a mite (Knemidokoptes jamaicensis) that can result in the birds losing their digits or entire feet, rendering them unable to perch, walk or feed.

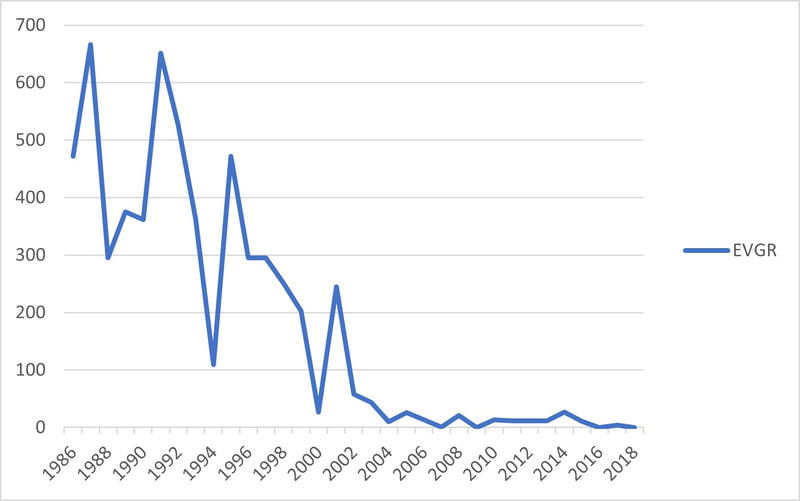

Locally, thanks to the ongoing efforts of Red Deer’s Christmas Bird Count compiler, Judy Boyd, we have Central Alberta CBC data summaries since 1986 (see graph) that confirm—even with peaks and valleys—an overall downward trend until the early 2000s, when numbers dropped dramatically. Sadly, no birds at all were noted on CBCs in 2009, 2016 and 2018. Recent sporadic reports of grosbeaks at feeders this winter, such as around Breton and near Morningside, are encouraging.

Given the long history that EBF has had with this species, I’d be interested in getting any reports of local sightings ([email protected]). Sightings can also be examined/posted on eBird (www.ebird.org). Finally, I encourage everyone to participate in this year’s Christmas Bird Count (CBC), which will be held on December 22. Contact Judy Boyd for details (403-358-1098). The CBC is a great way to contribute to science, get the family outdoors, and get children engaged in nature!

When I started at EBF in 1987, Charlie and Winnie were still feeding grosbeaks. During the winter of 1990-1991, while writing my first book (Winter Bird Feeding: An Alberta Guide), I enjoyed watching the Evening Grosbeaks at the feeders outside my office window. Alas, over the next few years they seemed to disappear. Even though the species is considered to be an irruptive migrant (absent one year, then abundant the next), their decline was widely reported across North America.

The story of Evening Grosbeak population dynamics is both interesting and puzzling. Rarely seen east of the Rockies before the mid-1800s, they then began moving eastward with each winter migration, reaching the east coast in the winter of 1910–1911. Their rapid expansion may have been facilitated by a new, abundant and secure winter food source—ornamental Box Elder shrubs that were widely planted in rural yards and urban subdivisions.

Thanks to citizen science initiatives such as Christmas Bird Counts and Project FeederWatch, anecdotal observations of population losses were backed up by data that confirmed both declines and range contractions: between 1988 and 2006, the number of FeederWatch sites reporting Evening Grosbeaks declined by 50%; at stations that continued to report them, numbers declined by 27%.

Many factors have been implicated in the decline, including climate change, large-scale forestry operations that remove the diverse old growth forests upon which they depend for nesting (in one study, no Evening Grosbeaks were found nesting in forests that were less than 100 years old), other habitat destruction and the aerial spraying for spruce budworm.

The birds are also prone to diseases, including a bacterium (Mycoplasma gallisepticum) as well as salmonellosis and West Nile virus. As if these afflictions aren’t enough, Evening Grobeaks are also susceptible to the parasitic infection by a mite (Knemidokoptes jamaicensis) that can result in the birds losing their digits or entire feet, rendering them unable to perch, walk or feed.

Locally, thanks to the ongoing efforts of Red Deer’s Christmas Bird Count compiler, Judy Boyd, we have Central Alberta CBC data summaries since 1986 (see graph) that confirm—even with peaks and valleys—an overall downward trend until the early 2000s, when numbers dropped dramatically. Sadly, no birds at all were noted on CBCs in 2009, 2016 and 2018. Recent sporadic reports of grosbeaks at feeders this winter, such as around Breton and near Morningside, are encouraging.

Given the long history that EBF has had with this species, I’d be interested in getting any reports of local sightings ([email protected]). Sightings can also be examined/posted on eBird (www.ebird.org). Finally, I encourage everyone to participate in this year’s Christmas Bird Count (CBC), which will be held on December 22. Contact Judy Boyd for details (403-358-1098). The CBC is a great way to contribute to science, get the family outdoors, and get children engaged in nature!

November 2019: Bohemian Waxwings

It is always a treat when a winter flock of Bohemian Waxwings suddenly descends on the cotoneaster bushes in our yard. No matter the weather, their constant trilling fills the air and they devour the berries with great flourish.

Like their namesakes—the gypsies of ancient Bohemia—Bohemian Waxwing are consummate nomads. They move south from their mountain/boreal nesting grounds for the winter, wandering great distances in a ceaseless quest for food.

Bohemians and their smaller, more svelte summer cousins, Cedar Waxwings, typically flock independently, but individuals of one species sometimes associate with flocks of the other. Many birders in Alberta carefully scan winter flocks of Bohemians to see if they can find any Cedars among them.

Waxwings are unusual among passerines in that they do not have a true song. However, they do issue a readily identifiable high-pitched, rapid, vibrato trill while perched or in flight. This trill (called the basic trill) has seven variations: social call, contact call, male and female courtship calls, injury call, begging call and disturbance call.

Bohemian Waxwings eat mostly sugary fruits but will supplement their diet with such protein-rich foods as insects, tree buds and the seeds of American elm. Their preferred winter fruits—which they pluck and eat either in pieces or swallow whole (sometimes after a ceremonial flip in the air!)—include juniper, mountain ash, hawthorn, rose hips, cranberry, highbush cranberry, ornamental crabapples, Russian olive and hedge cotoneaster. They will often drink water or eat snow after consuming dried berries. In the spring, they will feed on maple or birch sap drips and will also dine on catkins and tree/shrub blossoms.

It is well documented that Bohemian Waxwings can become intoxicated after consuming fermented berries, especially in late winter or early spring. While the birds have relatively large livers and can metabolize ethanol better than most bird species—they have high levels of alcohol dehydrogenase—they are sometimes seen staggering or fluttering about in a drunken state.

Since they are so abundant, and in winter can be quite docile, Bohemian Waxwings are often targeted by birds of prey, especially Merlins. It is thought that Merlins have increased in number and range because of this abundant prey base, which in turn has thrived because of the widespread planting of ornamental shrubs (especially crab apple and mountain ash) in urban and suburban backyards in the 1970s.

Sadly, Bohemian Waxwings are susceptible to collisions with windows, probably because ornamental fruit shrubs and trees are often planted near buildings. According to Medicine River Wildlife Centre, window collisions are highest in spring, apparently because window reflection patterns are affected by the angle of the sun.

While Bohemian Waxwings are not considered to be a common or typical backyard feeder species, some bird enthusiasts collect, freeze and then set out mountain ash berries and/or crabapples for them. They have also been observed bathing in open water or heated bird baths.

When I first met Charlie and Winnie Ellis, they shared stories about the great flocks of Bohemian Waxwings that visited their yard each winter. In addition to feeding on the many crabapple trees in Winnie’s orchard, the waxwings would receive extra-special treats: Charlie would go to town each week and buy cases of apples and large bags of raisins, which Winnie would mash up together and glob onto pie plates. Charlie would carry the plates outside to the waiting hordes. Luckily, one image remains of Charlie and their Bohemian friends.

Like their namesakes—the gypsies of ancient Bohemia—Bohemian Waxwing are consummate nomads. They move south from their mountain/boreal nesting grounds for the winter, wandering great distances in a ceaseless quest for food.

Bohemians and their smaller, more svelte summer cousins, Cedar Waxwings, typically flock independently, but individuals of one species sometimes associate with flocks of the other. Many birders in Alberta carefully scan winter flocks of Bohemians to see if they can find any Cedars among them.

Waxwings are unusual among passerines in that they do not have a true song. However, they do issue a readily identifiable high-pitched, rapid, vibrato trill while perched or in flight. This trill (called the basic trill) has seven variations: social call, contact call, male and female courtship calls, injury call, begging call and disturbance call.

Bohemian Waxwings eat mostly sugary fruits but will supplement their diet with such protein-rich foods as insects, tree buds and the seeds of American elm. Their preferred winter fruits—which they pluck and eat either in pieces or swallow whole (sometimes after a ceremonial flip in the air!)—include juniper, mountain ash, hawthorn, rose hips, cranberry, highbush cranberry, ornamental crabapples, Russian olive and hedge cotoneaster. They will often drink water or eat snow after consuming dried berries. In the spring, they will feed on maple or birch sap drips and will also dine on catkins and tree/shrub blossoms.

It is well documented that Bohemian Waxwings can become intoxicated after consuming fermented berries, especially in late winter or early spring. While the birds have relatively large livers and can metabolize ethanol better than most bird species—they have high levels of alcohol dehydrogenase—they are sometimes seen staggering or fluttering about in a drunken state.

Since they are so abundant, and in winter can be quite docile, Bohemian Waxwings are often targeted by birds of prey, especially Merlins. It is thought that Merlins have increased in number and range because of this abundant prey base, which in turn has thrived because of the widespread planting of ornamental shrubs (especially crab apple and mountain ash) in urban and suburban backyards in the 1970s.

Sadly, Bohemian Waxwings are susceptible to collisions with windows, probably because ornamental fruit shrubs and trees are often planted near buildings. According to Medicine River Wildlife Centre, window collisions are highest in spring, apparently because window reflection patterns are affected by the angle of the sun.

While Bohemian Waxwings are not considered to be a common or typical backyard feeder species, some bird enthusiasts collect, freeze and then set out mountain ash berries and/or crabapples for them. They have also been observed bathing in open water or heated bird baths.

When I first met Charlie and Winnie Ellis, they shared stories about the great flocks of Bohemian Waxwings that visited their yard each winter. In addition to feeding on the many crabapple trees in Winnie’s orchard, the waxwings would receive extra-special treats: Charlie would go to town each week and buy cases of apples and large bags of raisins, which Winnie would mash up together and glob onto pie plates. Charlie would carry the plates outside to the waiting hordes. Luckily, one image remains of Charlie and their Bohemian friends.

October 2019: Snow Geese

Fall is a wonderful time to witness one of nature’s many spectacles – the mass southerly migration of geese through the Canadian prairies.

While most of us are familiar with Canada geese (some populations are resident while others are migratory), two other goose species also move through the province in large numbers during fall migration: snow geese and greater white-fronted geese. Sometimes they travel; in single-species flocks, other times two or three species will journey together.

Snow geese occur in two forms, the white-colored light morphs and the blue-gray dark morphs. Since most individuals in any population are the white morphs, flocks of snow geese are easy to identify as they dazzle against a blue sky or sparkle amidst the subdued palette of a harvested field. Unlike Canada geese, which travel in classic “V” formation, snow geese travel in oscillating, loosely formed lines.

Snow geese breed across the Arctic tundra. All three populations (Western, Midcontinent and Eastern) were so low in the early 1900’s that they were given protected status; today, their populations have rebounded to such high numbers that they are actually causing severe habitat destruction across their breeding grounds. Hunting quotas have been increased in an effort to curb the population explosion.

When it is time to migrate, each snow goose population follows its own specific migration route, heading mostly due south from the breeding grounds to wintering sites at approximately the same longitude. The birds fly quickly and at high altitudes, making long stopovers at various staging areas along the way.

While resting on water, snow geese will often bunch together to create a large flotilla. Last week near Saskatoon, SK, we saw one flotilla of approximately 30,000 birds. When a Bald Eagle suddenly appeared over a nearby ridge, the entire flock lifted off in a cacophonous cloud. They circled noisily overhead before arcing back down to the water to create another raucous avian armada.

Like most wild birds, snow geese are too wary to allow close approach. However, a couple of falls ago, a friend and I were fortunate to encounter a small group of snow geese feeding in a wet roadside ditch. Using my vehicle as a blind, I was able to watch and photograph them at close range. We were amazed at how viciously they squabbled with each other and how voraciously they prodded the shoreline muck with their massive beaks. I later learned that this dining behaviour – called grubbing – is how they access the nutritious and fibrous rhizomes of various aquatic plant species. Interestingly, I also learned that food passes through a snow goose’s digestive tract in only an hour or two, resulting in them expelling 6 to 15 droppings per hour!

I am still trying to get good photos of greater white-fronted geese. When I get enough suitable images, I will do a future column about these abundant and interesting snow goose cousins.

While most of us are familiar with Canada geese (some populations are resident while others are migratory), two other goose species also move through the province in large numbers during fall migration: snow geese and greater white-fronted geese. Sometimes they travel; in single-species flocks, other times two or three species will journey together.

Snow geese occur in two forms, the white-colored light morphs and the blue-gray dark morphs. Since most individuals in any population are the white morphs, flocks of snow geese are easy to identify as they dazzle against a blue sky or sparkle amidst the subdued palette of a harvested field. Unlike Canada geese, which travel in classic “V” formation, snow geese travel in oscillating, loosely formed lines.

Snow geese breed across the Arctic tundra. All three populations (Western, Midcontinent and Eastern) were so low in the early 1900’s that they were given protected status; today, their populations have rebounded to such high numbers that they are actually causing severe habitat destruction across their breeding grounds. Hunting quotas have been increased in an effort to curb the population explosion.

When it is time to migrate, each snow goose population follows its own specific migration route, heading mostly due south from the breeding grounds to wintering sites at approximately the same longitude. The birds fly quickly and at high altitudes, making long stopovers at various staging areas along the way.

While resting on water, snow geese will often bunch together to create a large flotilla. Last week near Saskatoon, SK, we saw one flotilla of approximately 30,000 birds. When a Bald Eagle suddenly appeared over a nearby ridge, the entire flock lifted off in a cacophonous cloud. They circled noisily overhead before arcing back down to the water to create another raucous avian armada.

Like most wild birds, snow geese are too wary to allow close approach. However, a couple of falls ago, a friend and I were fortunate to encounter a small group of snow geese feeding in a wet roadside ditch. Using my vehicle as a blind, I was able to watch and photograph them at close range. We were amazed at how viciously they squabbled with each other and how voraciously they prodded the shoreline muck with their massive beaks. I later learned that this dining behaviour – called grubbing – is how they access the nutritious and fibrous rhizomes of various aquatic plant species. Interestingly, I also learned that food passes through a snow goose’s digestive tract in only an hour or two, resulting in them expelling 6 to 15 droppings per hour!

I am still trying to get good photos of greater white-fronted geese. When I get enough suitable images, I will do a future column about these abundant and interesting snow goose cousins.

September 2020: Least Chipmunks

A recent visit to the Nordegg area has rekindled my interest in Least Chipmunks. While there, I was able to spend a bit of time one sunny afternoon in the company of a chipmunk that was tackling some dandelion seed heads. I was amazed by its energy, the incredible dexterity of its tiny fingers, and the speed at which it ripped off the seeds.

Chipmunks can be distinguished from other squirrels by their small size, a pattern of five dark and four pale stripes down their backs, and alternating stripes on their faces. There are three species in Alberta but two (Yellow-pine and Red-tailed) are limited to the mountainous areas of the province.

Least Chipmunks eat nuts, seeds, leaves, grasses, flowers, insects and fungi. At backyard bird feeding stations, they will readily devour sunflower seeds and, if they happen upon a bird nest in the forest, will raid it. What they don’t eat on the spot, they gather in their large cheek pouches and pack off to store. They will horde bits of food in many different locations. This practice, called scatter-hording, hides the food from the prying eyes of other animals, including other chipmunks, and serves to ensure that numerous larder locations can be accessed during lean times. Unbeknownst to the chipmunks, this behaviour also serves to enhance forest biodiversity because some of the stored seeds inevitably germinate.

Least Chipmunks are diurnal, retreating to their snug underground burrows or tree cavities at night. They do hibernate in the winter, but instead of relying on stored fat to survive, they spend weeks in the fall filling up their winter burrows with massive stores of food. They dig these winter dens, which consist of one main passageway and one sleeping chamber, in the late summer. They will wake up periodically during the winter to feed from their well-stocked pantries.

While watching a pair of chipmunks a few summers ago at the old Nordegg mine site, I observed that they would regularly touch noses. Apparently sniffing is one of the many ways that chipmunks communicate with each other. Nonaggressive encounters involve nose touching and cheek/neck sniffing while flattened ears, fluffed tails and jerky body movements are displayed if the encounter is aggressive. Like other mammals, they will also sniff each other’s rears to obtain chemical information and display other typical mammalian postures to signify aggression, dominance or submission. They aren’t especially vocal, but will cry out if pursued by a predator, apparently willing to sacrifice their own life to warn others of grave danger. Interestingly, in areas where their ranges overlap with woodchucks, they will respond to the woodchucks’ alarm calls. Woodchucks also recognize the chipmunks’ alarm calls but – being larger and thus less vulnerable – don’t usually pay them much heed.

I also observed that the Nordegg chipmunks scampered around on the old concrete foundations, stopping occasionally to lick at the substrate. It is likely that the weathered cement provided some type of appealing salt or mineral.

The Least Chipmunk has a wide distribution across Alberta, but I rarely see them except in the west country. It is likely that local populations across the agricultural areas of the province have been wiped out by habitat destruction and cats. If you share your yard or farm with these remarkable little wild neighbours, I would appreciate hearing from you. It would be interesting to get details on their local distribution.

Chipmunks can be distinguished from other squirrels by their small size, a pattern of five dark and four pale stripes down their backs, and alternating stripes on their faces. There are three species in Alberta but two (Yellow-pine and Red-tailed) are limited to the mountainous areas of the province.

Least Chipmunks eat nuts, seeds, leaves, grasses, flowers, insects and fungi. At backyard bird feeding stations, they will readily devour sunflower seeds and, if they happen upon a bird nest in the forest, will raid it. What they don’t eat on the spot, they gather in their large cheek pouches and pack off to store. They will horde bits of food in many different locations. This practice, called scatter-hording, hides the food from the prying eyes of other animals, including other chipmunks, and serves to ensure that numerous larder locations can be accessed during lean times. Unbeknownst to the chipmunks, this behaviour also serves to enhance forest biodiversity because some of the stored seeds inevitably germinate.

Least Chipmunks are diurnal, retreating to their snug underground burrows or tree cavities at night. They do hibernate in the winter, but instead of relying on stored fat to survive, they spend weeks in the fall filling up their winter burrows with massive stores of food. They dig these winter dens, which consist of one main passageway and one sleeping chamber, in the late summer. They will wake up periodically during the winter to feed from their well-stocked pantries.

While watching a pair of chipmunks a few summers ago at the old Nordegg mine site, I observed that they would regularly touch noses. Apparently sniffing is one of the many ways that chipmunks communicate with each other. Nonaggressive encounters involve nose touching and cheek/neck sniffing while flattened ears, fluffed tails and jerky body movements are displayed if the encounter is aggressive. Like other mammals, they will also sniff each other’s rears to obtain chemical information and display other typical mammalian postures to signify aggression, dominance or submission. They aren’t especially vocal, but will cry out if pursued by a predator, apparently willing to sacrifice their own life to warn others of grave danger. Interestingly, in areas where their ranges overlap with woodchucks, they will respond to the woodchucks’ alarm calls. Woodchucks also recognize the chipmunks’ alarm calls but – being larger and thus less vulnerable – don’t usually pay them much heed.

I also observed that the Nordegg chipmunks scampered around on the old concrete foundations, stopping occasionally to lick at the substrate. It is likely that the weathered cement provided some type of appealing salt or mineral.

The Least Chipmunk has a wide distribution across Alberta, but I rarely see them except in the west country. It is likely that local populations across the agricultural areas of the province have been wiped out by habitat destruction and cats. If you share your yard or farm with these remarkable little wild neighbours, I would appreciate hearing from you. It would be interesting to get details on their local distribution.

August 2020: Osprey

Ospreys are fascinating birds. Their crisp plumage, large yellow eyes, loping flight and incredible hunting skills make them an interesting species to observe.

The population of these fish-eating hawks rebounded following the ban on DDT in 1985. They can now be commonly seen patrolling waterways and lakes across North America, with most large Alberta lakes and rivers supporting healthy numbers.

Ospreys build their nests in tall trees and on a variety of human-made structures, including oilfield equipment, buildings and power poles. Power poles are dangerous as the nests can catch on fire and the birds risk being electrocuted. To address this problem, power companies and local conservationists have worked together in many areas to place deterrents on poles and to erect wooden nesting platforms. These alternate nesting locations are readily used by the birds and represent a win-win situation for all involved.

Ospreys have remarkable adaptations that enable them to fish effectively. They can dive down into the water from a height of 40 m and will plummet, feet first, below the water surface to snag a fish. They grab the fish with their sharp talons, then use the backward-pointing spines on the soles of their feet to prevent it from slipping out. If the fish is large, they struggle to get airborne again. Interestingly, they maximize aerodynamics while in flight by using an opposable outer toe to rotate the fish, so it is facing forward as they fly. The males provide most of the food for the female and young. He usually eats the head of the fish before delivering the rest of the carcass back to his family.

Since Ospreys arrive later in the spring than local Canada Geese, ownership battles often erupt when an Osprey pair discover that a goose has taken up residence on "their" nest. If the nesting goose refuses to leave, some pairs have been known to delay nesting until the goslings fledge.

Recent research using satellite transmitters has revealed that juvenile Ospreys will wander, loiter and even get lost on migration while adults fly faster and take more direct routes to and from their wintering grounds. Our western birds overwinter in Central America while eastern birds migrate all the way down to South America.

I have seen many Osprey nests and have observed that the bulky nesting material often includes large tangles of discarded baler twine and fishing line. At a nest near Sylvan Lake, I also noticed that one adult had a piece of twine wrapped around its foot. These are sobering examples of how discarded plastic poses a hazard to our environment and wildlife.

The next time you see an Osprey fishing or sitting atop a nest, take a bit of time to observe and appreciate these magnificent wild neighbours.

The population of these fish-eating hawks rebounded following the ban on DDT in 1985. They can now be commonly seen patrolling waterways and lakes across North America, with most large Alberta lakes and rivers supporting healthy numbers.

Ospreys build their nests in tall trees and on a variety of human-made structures, including oilfield equipment, buildings and power poles. Power poles are dangerous as the nests can catch on fire and the birds risk being electrocuted. To address this problem, power companies and local conservationists have worked together in many areas to place deterrents on poles and to erect wooden nesting platforms. These alternate nesting locations are readily used by the birds and represent a win-win situation for all involved.

Ospreys have remarkable adaptations that enable them to fish effectively. They can dive down into the water from a height of 40 m and will plummet, feet first, below the water surface to snag a fish. They grab the fish with their sharp talons, then use the backward-pointing spines on the soles of their feet to prevent it from slipping out. If the fish is large, they struggle to get airborne again. Interestingly, they maximize aerodynamics while in flight by using an opposable outer toe to rotate the fish, so it is facing forward as they fly. The males provide most of the food for the female and young. He usually eats the head of the fish before delivering the rest of the carcass back to his family.

Since Ospreys arrive later in the spring than local Canada Geese, ownership battles often erupt when an Osprey pair discover that a goose has taken up residence on "their" nest. If the nesting goose refuses to leave, some pairs have been known to delay nesting until the goslings fledge.

Recent research using satellite transmitters has revealed that juvenile Ospreys will wander, loiter and even get lost on migration while adults fly faster and take more direct routes to and from their wintering grounds. Our western birds overwinter in Central America while eastern birds migrate all the way down to South America.

I have seen many Osprey nests and have observed that the bulky nesting material often includes large tangles of discarded baler twine and fishing line. At a nest near Sylvan Lake, I also noticed that one adult had a piece of twine wrapped around its foot. These are sobering examples of how discarded plastic poses a hazard to our environment and wildlife.

The next time you see an Osprey fishing or sitting atop a nest, take a bit of time to observe and appreciate these magnificent wild neighbours.