Red Deer Advocate-2021

December 2021 -The Brilliance of Camouflage

A few years ago, on a bright sunny fall afternoon, we were hiking along a quiet trail in the west country. Suddenly, we detected some movement up on a small side hill. Lifting the binoculars for a closer look, I made out the form of a Ruffed Grouse, strolling slowly in our direction. I was amazed at how remarkably camouflaged it was against the vegetation, especially when it stopped. Luckily, it continued in our direction, so I was able to get some photographs and marvel at how closely it matched its surroundings.

Each November, I make a pilgrimage to Kananaskis Country to look for White-tailed Ptarmigan. These species—unlike their Ruffed Grouse cousins, which remain cryptically colored all year-round—molt each fall into pure white plumage. Thus attired, they become “one” with the high-country snowpack. When tucked up against a tree, only the most careful observers can detect the tiny beak and coal black eyes that reveal their presence. As the snow melts in the spring, these brilliant white birds slowly transform back into drab browns and grays, colours that make them equally difficult to detect in their mountainous summer homes.

Snowy Owls remain white all year-round. They nest in the Arctic, where the brief nesting season doesn’t warrant a plumage change. And when they come south for the winter, they are already suitably attired for our snowy landscape. While they blend in well when sitting in a snow-covered field, their habit of perching atop power poles and signposts makes them highly visible. With few predators to worry about, they aren’t so concerned about being camouflaged.

Snowshoe Hares are the classic example of a species that changes colour with the seasons in order to maximize the benefits of camouflage. Unlike feathers, which can be molted out quite quickly, it can take weeks for fur to change colour. If the winter snow arrival or melt doesn’t coincide with their molt schedule, individuals stand out against like beacons against the “wrong” background. In these cases, the adaptation to molt comes with increased risk.

Each November, I make a pilgrimage to Kananaskis Country to look for White-tailed Ptarmigan. These species—unlike their Ruffed Grouse cousins, which remain cryptically colored all year-round—molt each fall into pure white plumage. Thus attired, they become “one” with the high-country snowpack. When tucked up against a tree, only the most careful observers can detect the tiny beak and coal black eyes that reveal their presence. As the snow melts in the spring, these brilliant white birds slowly transform back into drab browns and grays, colours that make them equally difficult to detect in their mountainous summer homes.

Snowy Owls remain white all year-round. They nest in the Arctic, where the brief nesting season doesn’t warrant a plumage change. And when they come south for the winter, they are already suitably attired for our snowy landscape. While they blend in well when sitting in a snow-covered field, their habit of perching atop power poles and signposts makes them highly visible. With few predators to worry about, they aren’t so concerned about being camouflaged.

Snowshoe Hares are the classic example of a species that changes colour with the seasons in order to maximize the benefits of camouflage. Unlike feathers, which can be molted out quite quickly, it can take weeks for fur to change colour. If the winter snow arrival or melt doesn’t coincide with their molt schedule, individuals stand out against like beacons against the “wrong” background. In these cases, the adaptation to molt comes with increased risk.

November 2021 - Exploring Central Alberta

Last spring, the Red Deer River Naturalists (RDRN)—the oldest natural history organization in Alberta—launched a very exciting initiative to encourage people, especially the residents of Central Alberta, to get out and explore our own “backyard.” Called Nature Central: Celebrating our Wild Alberta Parklands, the goal of the program was to identify and collect information about all the various protected areas near Red Deer, promote the respectful and non-consumptive enjoyment of these properties, and to promote environmental awareness by leading walks and hosting family nature programs. We hired a young Naturalist in Residence (Shaye Hill) and an Assistant Naturalist (Sherry Scheunert) to do the work. I offered to be the volunteer liaison for the project, so it was my privilege to explore some of these beautiful areas and to participate in many of the interesting walks and events. Since the properties are owned by various agencies (e.g., municipalities) and non-profit organizations (e.g., Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC), Ducks Unlimited Canada, Alberta Conservation Association, Alberta Fish and Game Association, etc.), it was important to ensure that the program complemented and complied with their land management protocols. All stakeholders welcomed our involvement. To our surprise, the Nature Central team documented a total of 169 parcels of protected land within 100 km of the city, most of which are publicly accessible! All properties are listed on the www.naturecentral.org website. The properties range from those that have facilities, parking and trails to parcels that are off the beaten path, have no trails or signage and require some navigation skills to access. Most properties can be visited on a drop-in basis, although access to properties owned by NCC needs to be booked through their website (www.connect2nature.ca). The RDRN plans to continue and even expand Nature Central next spring and summer. We hope that more and more people will discover, explore and respectfully enjoy these natural gems that are in our own big beautiful backyard. If you would like more information about Nature Central, please don’t hesitate to contact me at [email protected]. IMAGE: RAVEN BROOD STATION, CAROLINE AB. |

September - 2021 - Feeding Peanuts

Fall is bird feeding time! While some folks keep bird feeders stocked year-round, most bird enthusiasts turn their attention to backyard birds in the fall, after the summer-nesting birds have flown south and our resident birds start setting up their winter territories.

I plan to dedicate a few upcoming columns to the topic of backyard birds and bird feeding, starting with one of the most popular and nutritious offerings: peanuts.

Peanuts, which have high fat and protein content, are appealing to many insect-and seed-eating birds. They can be served unshelled, shelled, chipped (broken pieces) or in the form of peanut butter. Peanuts in the shell are a magnet for Blue Jays. At this time of year, they will eagerly descend on offerings of peanuts, packing away any that they don’t immediately consume. They cache these excess seeds in nearby hiding spots, saving them for later in the winter when they’ll retrieve and eat them. I usually place a handful of unshelled peanuts in a tray feeder for the Blue Jays, then fill up a peanut ring—a clever dispenser designed to require some aerial acrobatics before these expensive delicacies can be accessed.

The two types of shelled peanuts are those with the skin on (redskin) or off (blanched). The blanched ones are slightly more expensive than the redskins but are easier for chickadees and nuthatches to eat. I often set out a few shelled peanuts on a tray feeder as a special treat but ration out the rest from metal mesh tube feeders. These feeders are busy all day long with a steady parade of chickadees, nuthatches and several species of woodpeckers vying for a dining spot.

Peanut butter can be served as a stand-alone offering or mixed with suet/lard and dispensed from special suet logs or slathered directly as “bark butter” on tree trunks. This mixture will attract additional species, including kinglets and creepers.

Squirrels also love peanuts as well as peanut butter, so metal feeders, weight-activated feeders or special squirrel baffles can be used to deter these voracious competitors.

Note that wet peanuts can become contaminated with aflatoxins (naturally occurring toxins produced by certain species of fungi that flourish on some plants under humid conditions) so be sure to discard any that become soggy.

Backyard bird feeding is a wonderful way to bring nature into our own yards and gardens. If you have any questions about bird feeding, bird feeder styles or backyard bird identification, feel free to contact me.

I plan to dedicate a few upcoming columns to the topic of backyard birds and bird feeding, starting with one of the most popular and nutritious offerings: peanuts.

Peanuts, which have high fat and protein content, are appealing to many insect-and seed-eating birds. They can be served unshelled, shelled, chipped (broken pieces) or in the form of peanut butter. Peanuts in the shell are a magnet for Blue Jays. At this time of year, they will eagerly descend on offerings of peanuts, packing away any that they don’t immediately consume. They cache these excess seeds in nearby hiding spots, saving them for later in the winter when they’ll retrieve and eat them. I usually place a handful of unshelled peanuts in a tray feeder for the Blue Jays, then fill up a peanut ring—a clever dispenser designed to require some aerial acrobatics before these expensive delicacies can be accessed.

The two types of shelled peanuts are those with the skin on (redskin) or off (blanched). The blanched ones are slightly more expensive than the redskins but are easier for chickadees and nuthatches to eat. I often set out a few shelled peanuts on a tray feeder as a special treat but ration out the rest from metal mesh tube feeders. These feeders are busy all day long with a steady parade of chickadees, nuthatches and several species of woodpeckers vying for a dining spot.

Peanut butter can be served as a stand-alone offering or mixed with suet/lard and dispensed from special suet logs or slathered directly as “bark butter” on tree trunks. This mixture will attract additional species, including kinglets and creepers.

Squirrels also love peanuts as well as peanut butter, so metal feeders, weight-activated feeders or special squirrel baffles can be used to deter these voracious competitors.

Note that wet peanuts can become contaminated with aflatoxins (naturally occurring toxins produced by certain species of fungi that flourish on some plants under humid conditions) so be sure to discard any that become soggy.

Backyard bird feeding is a wonderful way to bring nature into our own yards and gardens. If you have any questions about bird feeding, bird feeder styles or backyard bird identification, feel free to contact me.

August - 2021 - Marsh Wrens

Earlier this month, while enjoying an early morning kayak along the shallows on Buffalo Lake, we saw two juvenile Marsh Wrens. It was intriguing to watch them, but their frenetic movements and habit of skulking low along the shoreline made photography difficult.

When we returned a few hours later to our put-in spot near a sandy bank, we noticed several more Marsh Wrens, both juveniles and adults, flitting about. Although I have found their nests, heard the males sing and have caught occasional glimpses of them over the years, this was my first time seeing these beautiful little marsh dwellers in full view.

We soon noticed that they were all taking turns dust bathing in the sand! Dust bathing, which is practised by many bird species, helps (like snow or water bathing) keep the feathers in good condition and control ectoparasites.

One of the four active bathing bowls was level with the kayak, so from this unique ringside seat, we were able to sit quietly and enjoy some very interesting wren watching. We observed that each energetic dust bath lasted from a few seconds to almost a minute. We also noted several conflicts over bathing rights, with dominant birds chasing off subordinates.

The birds quickly realized that we were no threat, so, in addition to watching them bathe, we were treated to a few close encounters as adults hopped into full view and a couple juveniles even landed adjacent to the kayak, their tiny legs splayed out between two bullrushes.

An hour and several hundred images later, and with storm clouds looming, we reluctantly bid adieu to these little denizens of the marsh.

When I returned home, I spent some time reading about the species. I learned that Marsh Wrens are found in cattail marshes and wet meadows in all Alberta natural regions except the mountains. Males arrive first on the breeding ground and set to work weaving several complicated dome-shaped nests from strips of cattails, sedges and grasses. When the females arrive, the males sing their buzzy trill, cock their tails, and escort a potential mate around to inspect their handiwork. The female selects a nest (or in some cases builds her own) and they both aggressively defend the territory. Male Marsh Wrens are grand philanderers, and both males and females will destroy their neighbours’ eggs and even kill the nestlings. They have also been known to destroy the nests of other marsh birds. Despite these seemingly unsavoury habits, Marsh Wrens are remarkable and fascinating wild neighbours.

When we returned a few hours later to our put-in spot near a sandy bank, we noticed several more Marsh Wrens, both juveniles and adults, flitting about. Although I have found their nests, heard the males sing and have caught occasional glimpses of them over the years, this was my first time seeing these beautiful little marsh dwellers in full view.

We soon noticed that they were all taking turns dust bathing in the sand! Dust bathing, which is practised by many bird species, helps (like snow or water bathing) keep the feathers in good condition and control ectoparasites.

One of the four active bathing bowls was level with the kayak, so from this unique ringside seat, we were able to sit quietly and enjoy some very interesting wren watching. We observed that each energetic dust bath lasted from a few seconds to almost a minute. We also noted several conflicts over bathing rights, with dominant birds chasing off subordinates.

The birds quickly realized that we were no threat, so, in addition to watching them bathe, we were treated to a few close encounters as adults hopped into full view and a couple juveniles even landed adjacent to the kayak, their tiny legs splayed out between two bullrushes.

An hour and several hundred images later, and with storm clouds looming, we reluctantly bid adieu to these little denizens of the marsh.

When I returned home, I spent some time reading about the species. I learned that Marsh Wrens are found in cattail marshes and wet meadows in all Alberta natural regions except the mountains. Males arrive first on the breeding ground and set to work weaving several complicated dome-shaped nests from strips of cattails, sedges and grasses. When the females arrive, the males sing their buzzy trill, cock their tails, and escort a potential mate around to inspect their handiwork. The female selects a nest (or in some cases builds her own) and they both aggressively defend the territory. Male Marsh Wrens are grand philanderers, and both males and females will destroy their neighbours’ eggs and even kill the nestlings. They have also been known to destroy the nests of other marsh birds. Despite these seemingly unsavoury habits, Marsh Wrens are remarkable and fascinating wild neighbours.

July - 2021 - Spotted Sandpipers

On one of my early morning kayaks on Sylvan Lake in late June, I had an unexpected and wonderful wildlife encounter. It was one of those perfect summer mornings that I had the privilege of sharing with several families of ducks, a Great Blue Heron, a Bald Eagle and many songbird species.

As I approached the west shoreline of the lake, I could see a pair of Spotted Sandpipers bobbing along a small stretch of beach. As I paddled closer, two little fluff balls suddenly materialized! The adults, alarmed by my approach, soon sent the young scurrying back into the thick shoreline grass. I noted the location and paddled on.

I returned to the same spot on my way back. This time, the adults—although aware of my presence—were not overly alarmed. I let the kayak drift closer and, with camera in hand, hoped to at least catch another glimpse of the young. Suddenly, four tiny sandpipers emerged. Daintily tiptoeing on garishly long toes and bobbing their shaggy little tails, these precious creatures—oblivious to my presence—pecked and poked for their food, stretched, groomed, sipped dew drops from the undersides of leaves, and one even napped for a few moments.

After several glorious minutes, they retreated into the grass and disappeared. I backed away quietly and paddled home. What an “awe”some way to start a day!

Spotted Sandpipers, unlike other hard-to-recognize shorebirds*, can be easily identified by their spotted chests and teetering gait. The most widespread sandpiper on the continent, they can be found in most habitats as long they it contains a stretch of shoreline, some semi-open habitat, and patches of dense vegetation.

Female Spotted Sandpipers have a unique breeding strategy: they arrive on territory earlier than the males in the spring, establish their own territories and—early in the breeding season—experience a surge in testosterone levels. This hormone increase may account for them being aggressive and, in some cases, polyandrous. Some females will mate with up to four males, which then incubate the eggs and care for the young. Amazingly, females can store sperm for up to a month and, because they have so many mates, the young in each clutch may have different fathers.

Since that wonderful early morning paddle, I have had the pleasure of many more kayak trips around Central Alberta. Each trip has been enriched by encountering and watching these interesting and engaging little shorebirds.

*Nature Alberta has published a helpful guide to shorebirds in Alberta. It can be downloaded at https://naturealberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2019_NatureAlberta_ShorebirdsChecklist_web.pdf

As I approached the west shoreline of the lake, I could see a pair of Spotted Sandpipers bobbing along a small stretch of beach. As I paddled closer, two little fluff balls suddenly materialized! The adults, alarmed by my approach, soon sent the young scurrying back into the thick shoreline grass. I noted the location and paddled on.

I returned to the same spot on my way back. This time, the adults—although aware of my presence—were not overly alarmed. I let the kayak drift closer and, with camera in hand, hoped to at least catch another glimpse of the young. Suddenly, four tiny sandpipers emerged. Daintily tiptoeing on garishly long toes and bobbing their shaggy little tails, these precious creatures—oblivious to my presence—pecked and poked for their food, stretched, groomed, sipped dew drops from the undersides of leaves, and one even napped for a few moments.

After several glorious minutes, they retreated into the grass and disappeared. I backed away quietly and paddled home. What an “awe”some way to start a day!

Spotted Sandpipers, unlike other hard-to-recognize shorebirds*, can be easily identified by their spotted chests and teetering gait. The most widespread sandpiper on the continent, they can be found in most habitats as long they it contains a stretch of shoreline, some semi-open habitat, and patches of dense vegetation.

Female Spotted Sandpipers have a unique breeding strategy: they arrive on territory earlier than the males in the spring, establish their own territories and—early in the breeding season—experience a surge in testosterone levels. This hormone increase may account for them being aggressive and, in some cases, polyandrous. Some females will mate with up to four males, which then incubate the eggs and care for the young. Amazingly, females can store sperm for up to a month and, because they have so many mates, the young in each clutch may have different fathers.

Since that wonderful early morning paddle, I have had the pleasure of many more kayak trips around Central Alberta. Each trip has been enriched by encountering and watching these interesting and engaging little shorebirds.

*Nature Alberta has published a helpful guide to shorebirds in Alberta. It can be downloaded at https://naturealberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2019_NatureAlberta_ShorebirdsChecklist_web.pdf

June - 2021 - Sandhill Crane Hatch

Sandhill Cranes nest in the boreal forest regions of Alberta, usually in isolated marshy areas surrounded by forest or shrubs. Fortunately, there is still sufficient Sandhill Crane habitat remaining in our west country to support a healthy nesting population.

Three years ago, a pair of Sandhill Cranes nested close to the observation tower at Medicine River Wildlife Centre south of Raven. Several local naturalists watched and photographed two colts hatch over a period of two days. It was a memorable experience.

This year, a pair chose to build their nest in a fairly visible location at the edge of a slough south of Condor. The nest was tucked behind some cattails, making photography and detailed observations challenging. However, it was still a treat to be able to watch them at close range. During the month-long incubation period, the adults took turns sitting motionless on their precious cargo, enduring the extremes of vicious rainstorms and extreme heat. Both sexes incubate, so when one parent was on egg duty, the other could usually be seen standing quietly nearby.

The first colt hatched on Monday, May 31 with the second one arriving on Tuesday evening, June 1. On the morning of June 2, a few of us gathered before daybreak to observe the proceedings. Not much happened until about 6:30 AM, when the male—who had been watching from afar—sauntered up to the nest. The female stood up as he approached, and the colts could be seen scampering about on the sodden nest. Suddenly, Pa opened his wings and did (what appeared to be) a gleeful leap into the air. Ma followed suit, also leaping into the air with her giant wings flapping. They then settled down to feed the young, delicately offering them bits of eggshell and small pieces of food gleaned from around the nest area.

Suddenly, to our delight and astonishment, both adults lifted their heads to the sky and belted out a hearty duet, a thunderous and joyful avian birth announcement. It was an honour to witness this ancestral ritual, a proclamation that has echoed across swamps for millennia. Two more duets followed between feedings before the proud parents led their rusty little charges off into the swamp. By 7:45 AM we had packed up our cameras, offered thanks to the cranes and—with joyful hearts—got on with our day.

Three years ago, a pair of Sandhill Cranes nested close to the observation tower at Medicine River Wildlife Centre south of Raven. Several local naturalists watched and photographed two colts hatch over a period of two days. It was a memorable experience.

This year, a pair chose to build their nest in a fairly visible location at the edge of a slough south of Condor. The nest was tucked behind some cattails, making photography and detailed observations challenging. However, it was still a treat to be able to watch them at close range. During the month-long incubation period, the adults took turns sitting motionless on their precious cargo, enduring the extremes of vicious rainstorms and extreme heat. Both sexes incubate, so when one parent was on egg duty, the other could usually be seen standing quietly nearby.

The first colt hatched on Monday, May 31 with the second one arriving on Tuesday evening, June 1. On the morning of June 2, a few of us gathered before daybreak to observe the proceedings. Not much happened until about 6:30 AM, when the male—who had been watching from afar—sauntered up to the nest. The female stood up as he approached, and the colts could be seen scampering about on the sodden nest. Suddenly, Pa opened his wings and did (what appeared to be) a gleeful leap into the air. Ma followed suit, also leaping into the air with her giant wings flapping. They then settled down to feed the young, delicately offering them bits of eggshell and small pieces of food gleaned from around the nest area.

Suddenly, to our delight and astonishment, both adults lifted their heads to the sky and belted out a hearty duet, a thunderous and joyful avian birth announcement. It was an honour to witness this ancestral ritual, a proclamation that has echoed across swamps for millennia. Two more duets followed between feedings before the proud parents led their rusty little charges off into the swamp. By 7:45 AM we had packed up our cameras, offered thanks to the cranes and—with joyful hearts—got on with our day.

May - 2021 - Duck Love

Duck Love

Spring is all about renewal and rebirth. Not only are we being treated to spring flowers and the fresh flush of green grass and leaves, those who spend time out in nature can also witness our wild neighbours making and raising babies.

I had a good fortune earlier this month to witness and photograph the mating ritual of one of our most common duck species, the cavity-nesting Common Goldeneye. I spent many chilly but interesting hours in a bird blind, watching the birds undergo their complex and highly choreographed mating behaviours.

After watching three separate matings, I was able to recognize the pattern. The male would first undergo some ritualized displays in front of the female, including stretching his neck in the air, flipping water with his beak and doing some big leg stretches. The female, when she was ready, would signal her permission by lowering her head into the water. He would then rise up, circle to her back, and climb aboard. His weight would push her head under the surface for a few seconds, but she would then resurface and they would then twirl around in a tight circle for about 10-15 seconds. With the deed done, the male would then dismount and swim off, usually shaking his head. The female would swim away and take a vigorous bath. At some point she would fly off to lay her egg in a nearby duck box, then would return to his side for the rest of the day.

A pair of Common Goldneye typically stay together until she has laid her complete clutch of eggs. It is thought that they mate each morning. After the male is assured of his paternity, he abandons the female, who raises her family on her own.

Nature is so fascinating!

Myrna Pearman is a retired biologist and keen nature observer, writer and photographer. She can be reached at [email protected] www.myrnapearman.com

Spring is all about renewal and rebirth. Not only are we being treated to spring flowers and the fresh flush of green grass and leaves, those who spend time out in nature can also witness our wild neighbours making and raising babies.

I had a good fortune earlier this month to witness and photograph the mating ritual of one of our most common duck species, the cavity-nesting Common Goldeneye. I spent many chilly but interesting hours in a bird blind, watching the birds undergo their complex and highly choreographed mating behaviours.

After watching three separate matings, I was able to recognize the pattern. The male would first undergo some ritualized displays in front of the female, including stretching his neck in the air, flipping water with his beak and doing some big leg stretches. The female, when she was ready, would signal her permission by lowering her head into the water. He would then rise up, circle to her back, and climb aboard. His weight would push her head under the surface for a few seconds, but she would then resurface and they would then twirl around in a tight circle for about 10-15 seconds. With the deed done, the male would then dismount and swim off, usually shaking his head. The female would swim away and take a vigorous bath. At some point she would fly off to lay her egg in a nearby duck box, then would return to his side for the rest of the day.

A pair of Common Goldneye typically stay together until she has laid her complete clutch of eggs. It is thought that they mate each morning. After the male is assured of his paternity, he abandons the female, who raises her family on her own.

Nature is so fascinating!

Myrna Pearman is a retired biologist and keen nature observer, writer and photographer. She can be reached at [email protected] www.myrnapearman.com

April - 2021 - Muskrats

I have spent many pleasant hours muskrat watching. Time spent in the company of these industrious little rodents is so rewarding, especially at this time of year when they are highly active and often use ice edges for feeding and grooming.

Muskrats are large, semi-aquatic mice and get their name from specialized musk glands. One of the most widely distributed mammals in North America, they can occupy any wetland that is shallow enough to permit the growth of their aquatic food (cattails, bullrushes etc.) but is deep enough so that it does not freeze to the bottom during the winter.

Muskrats use their dexterous and hand-like front feet to dig out roots, burrow and hold their food. Their huge hind feet are not webbed, but have four long toes, each fringed with specialized hairs that act as paddles. Their tails are thin and flattened vertically.

Muskrats have two types of homes – lodges and bank burrows. Bank burrows are excavated while lodges are built by heaping mud and plant material into a mound, into which a chamber and one or two exit burrows are excavated. After freeze-up, they will also create feeding and resting stations (called push-ups) by chewing holes through the ice and topping these holes with vegetation and mud.

Muskrats are able to swim for long distances, thanks to the buoyancy provided by their luxurious waterproof fur. They are also efficient divers, able to hold their breath underwater for up to 15 minutes. During the winter, they can travel considerable distances under the ice, locating their food and then returning with it to a push-up – all in total darkness!

Muskrats are promiscuous, with males competing fiercely for females. These battles are easy to observe at this time of year, as many of our wetlands are either melted out or ringed by open water. Although I have not yet been able to capture any good photos of these altercations, I can confirm that they are vicious!

Female muskrats can have up to three litters per season, with five to 10 young per litter. The kits, born blind, naked and helpless, develop rapidly: within a week they are furred; by two weeks they explore on their own; at three weeks they are weaned; and by six weeks they are independent. Their lives are harsh and short; few muskrats live to be older than three years of age.

Muskrat populations fluctuate, with by a dramatic decrease occurring every few years. It appears that a population crash occurred three to four years ago, as very few muskrats were seen in local ponds. Last summer their numbers started rebounding, and I am heartened this spring to see that many potholes and small wetlands are once again busy with muskrat activity.

Muskrats are large, semi-aquatic mice and get their name from specialized musk glands. One of the most widely distributed mammals in North America, they can occupy any wetland that is shallow enough to permit the growth of their aquatic food (cattails, bullrushes etc.) but is deep enough so that it does not freeze to the bottom during the winter.

Muskrats use their dexterous and hand-like front feet to dig out roots, burrow and hold their food. Their huge hind feet are not webbed, but have four long toes, each fringed with specialized hairs that act as paddles. Their tails are thin and flattened vertically.

Muskrats have two types of homes – lodges and bank burrows. Bank burrows are excavated while lodges are built by heaping mud and plant material into a mound, into which a chamber and one or two exit burrows are excavated. After freeze-up, they will also create feeding and resting stations (called push-ups) by chewing holes through the ice and topping these holes with vegetation and mud.

Muskrats are able to swim for long distances, thanks to the buoyancy provided by their luxurious waterproof fur. They are also efficient divers, able to hold their breath underwater for up to 15 minutes. During the winter, they can travel considerable distances under the ice, locating their food and then returning with it to a push-up – all in total darkness!

Muskrats are promiscuous, with males competing fiercely for females. These battles are easy to observe at this time of year, as many of our wetlands are either melted out or ringed by open water. Although I have not yet been able to capture any good photos of these altercations, I can confirm that they are vicious!

Female muskrats can have up to three litters per season, with five to 10 young per litter. The kits, born blind, naked and helpless, develop rapidly: within a week they are furred; by two weeks they explore on their own; at three weeks they are weaned; and by six weeks they are independent. Their lives are harsh and short; few muskrats live to be older than three years of age.

Muskrat populations fluctuate, with by a dramatic decrease occurring every few years. It appears that a population crash occurred three to four years ago, as very few muskrats were seen in local ponds. Last summer their numbers started rebounding, and I am heartened this spring to see that many potholes and small wetlands are once again busy with muskrat activity.

March - 2021 - Spring is Here!

Although Central Alberta could have benefited from a deeper winter snowpack (let’s hope we get some dousing spring rains), it is uplifting to welcome the early return of warmth and life. The last remaining snow banks are melting, the ponds and rivers are starting to open up, and the pussy willows are erupting.

While I have yet to see a Mountain Bluebird, reports of first-of-season sightings have been pouring in since the earliest report was made of a male near Delburne on March 12. Since that time, images of bluebirds have been posted on social media from locations all around the province.

There are so many other signs of spring in Central Alberta! At the time of writing (March 25), I have observed that the Richardson’s Ground Squirrels, beavers and muskrats are out, the Snowshoe Hares are starting to turn brown, Common Ravens and House Sparrows are hauling nesting material, and Bald Eagles and Great Horned Owls are on their nests. Spring migrants are also starting to appear, especially the Canada Geese, which have arrived back in droves and are squabbling over wetland territories. Other early migrants include Northern Pintails, Red-tailed Hawks, Rough-legged Hawks, American Robins, Tundra and Trumpeter Swans, Dark-eyed Juncos and American Tree Sparrows. Most Common Redpolls, which over recent weeks had become increasingly tetchy with each other, have departed for their Arctic nesting grounds.

The Downy Woodpeckers in my yard are scrapping, the House Finches are singing enthusiastically, the Black-capped Chickadees have been issuing their cheeze-burger songs, male Northern Saw-whet Owls are singing their toot toot toot arias, the Northern Flickers have been kee keee keeing from the treetops, and our resident Pileated Woodpecker has found a resonant snag to tap out his distinctive Morse-code messages of love.

Within the next days and weeks, we will expect more and more migrants to start flooding back. If you are an observer of nature, I recommend you join the Red Deer River Naturalists Facebook group and share your first-of-season bird—and other spring—sightings!

While I have yet to see a Mountain Bluebird, reports of first-of-season sightings have been pouring in since the earliest report was made of a male near Delburne on March 12. Since that time, images of bluebirds have been posted on social media from locations all around the province.

There are so many other signs of spring in Central Alberta! At the time of writing (March 25), I have observed that the Richardson’s Ground Squirrels, beavers and muskrats are out, the Snowshoe Hares are starting to turn brown, Common Ravens and House Sparrows are hauling nesting material, and Bald Eagles and Great Horned Owls are on their nests. Spring migrants are also starting to appear, especially the Canada Geese, which have arrived back in droves and are squabbling over wetland territories. Other early migrants include Northern Pintails, Red-tailed Hawks, Rough-legged Hawks, American Robins, Tundra and Trumpeter Swans, Dark-eyed Juncos and American Tree Sparrows. Most Common Redpolls, which over recent weeks had become increasingly tetchy with each other, have departed for their Arctic nesting grounds.

The Downy Woodpeckers in my yard are scrapping, the House Finches are singing enthusiastically, the Black-capped Chickadees have been issuing their cheeze-burger songs, male Northern Saw-whet Owls are singing their toot toot toot arias, the Northern Flickers have been kee keee keeing from the treetops, and our resident Pileated Woodpecker has found a resonant snag to tap out his distinctive Morse-code messages of love.

Within the next days and weeks, we will expect more and more migrants to start flooding back. If you are an observer of nature, I recommend you join the Red Deer River Naturalists Facebook group and share your first-of-season bird—and other spring—sightings!

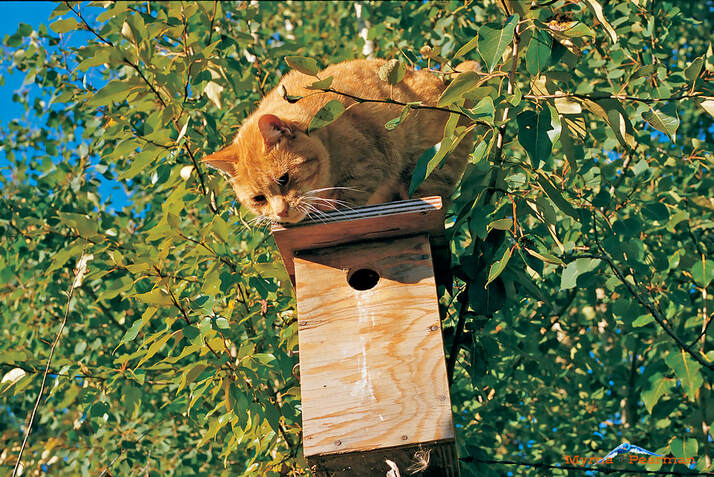

February - 2021 - Cats

The City of Red Deer recently asked for input into their future animal bylaws. They were seeking citizen feedback about keeping animals in the city – “everything from cats to bees to chickens.”

I don’t have much to say about bees or chickens, but I have done enough research over the years into the cat-wildlife issue that I feel qualified to share some facts. The City updated their cat bylaw in 1996, but state that it needs updating to address current issues.

When I wrote the book NatureScape Alberta: Creating and Caring for Wildlife at Home in 2000, the issue of cat predation on birds was just starting to be taken seriously, with several organizations across North America starting to raise the alarm bells. By the time I wrote Backyard Bird Feeding: An Alberta Guide fifteen years later, the issue was well-researched and several conservation organizations around the continent were publishing research papers and launching education campaigns to encourage the public to fully appreciate the seriousness of the situation.

Before I go further, I want to stress that I am not a cat hater. I am BOTH a bird lover and a cat lover. The information I share here is not to disparage cats or cat owners, but to help raise awareness about the very serious ecological threat posed by free-roaming cats.

Scientists now have declared that outdoor domestic cats are a recognized threat to global biodiversity, having contributed to the extinction of 63 species of birds, mammals and reptiles in the wild. Predation by domestic cats is the number-one direct, human-caused threat to birds in the U.S. and Canada and fact, the ecological threat posed by cats is so critical that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists domestic cats as one of the world’s worst non-native invasive species. It is estimated that 100 to 350 million birds are killed annually in Canada by five to 10 million outdoor cats.

Over the years, I’ve given many presentations about backyard biodiversity. When I talk about cats, I stress three points:

1. Cats kill even when they are well fed: their predatory instinct – which never shuts off - is not associated with food.

2. Bells and declawing don’t work—declawing is cruel and declawed cats can still bat birds out of the air. Bells are useless because cats learn to move without activating the bell. And birds have no idea that a bell means danger until it is too late.

3. Even if a cat catches a bird and the bird gets away/is pulled from the cat’s mouth, the bird’s skin has likely been punctured and it will die anyway due to bacteria transmitted from the cat’s mouth.

Letting cats roam unsupervised outdoors isn’t just bad for birds (or small mammals, reptiles and amphibians); it’s bad for the cats too. Disease, getting run over by vehicles, getting eaten by coyotes, foxes and owls, and contracting diseases are just a few of the threats that outdoor cats face. There is no doubt that indoor cats live longer and happier lives than outdoor ones.

The solution to roaming cats is quite simple – keep cats indoors or let them be outdoors on a tether or leash or kept in an outdoor run. These outdoor runs, often called catios, are easy to build (an online search will yield hundreds of plans) represent a win-win situation because they protect wildlife while still giving the cats the opportunity to enjoy being outside.

Let’s hope that the citizens of Red Deer gave informed feedback on the issue of roaming cats, and that bylaws will be updated to both protect biodiversity and respect cats and cat owners. For more information on this issue, some good websites to start with are https://abcbirds.org/program/cats-indoors/cats-and-birds/ , http://www.ace-eco.org/vol8/iss2/art3/#estimated and https://catsandbirds.ca/

I don’t have much to say about bees or chickens, but I have done enough research over the years into the cat-wildlife issue that I feel qualified to share some facts. The City updated their cat bylaw in 1996, but state that it needs updating to address current issues.

When I wrote the book NatureScape Alberta: Creating and Caring for Wildlife at Home in 2000, the issue of cat predation on birds was just starting to be taken seriously, with several organizations across North America starting to raise the alarm bells. By the time I wrote Backyard Bird Feeding: An Alberta Guide fifteen years later, the issue was well-researched and several conservation organizations around the continent were publishing research papers and launching education campaigns to encourage the public to fully appreciate the seriousness of the situation.

Before I go further, I want to stress that I am not a cat hater. I am BOTH a bird lover and a cat lover. The information I share here is not to disparage cats or cat owners, but to help raise awareness about the very serious ecological threat posed by free-roaming cats.

Scientists now have declared that outdoor domestic cats are a recognized threat to global biodiversity, having contributed to the extinction of 63 species of birds, mammals and reptiles in the wild. Predation by domestic cats is the number-one direct, human-caused threat to birds in the U.S. and Canada and fact, the ecological threat posed by cats is so critical that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists domestic cats as one of the world’s worst non-native invasive species. It is estimated that 100 to 350 million birds are killed annually in Canada by five to 10 million outdoor cats.

Over the years, I’ve given many presentations about backyard biodiversity. When I talk about cats, I stress three points:

1. Cats kill even when they are well fed: their predatory instinct – which never shuts off - is not associated with food.

2. Bells and declawing don’t work—declawing is cruel and declawed cats can still bat birds out of the air. Bells are useless because cats learn to move without activating the bell. And birds have no idea that a bell means danger until it is too late.

3. Even if a cat catches a bird and the bird gets away/is pulled from the cat’s mouth, the bird’s skin has likely been punctured and it will die anyway due to bacteria transmitted from the cat’s mouth.

Letting cats roam unsupervised outdoors isn’t just bad for birds (or small mammals, reptiles and amphibians); it’s bad for the cats too. Disease, getting run over by vehicles, getting eaten by coyotes, foxes and owls, and contracting diseases are just a few of the threats that outdoor cats face. There is no doubt that indoor cats live longer and happier lives than outdoor ones.

The solution to roaming cats is quite simple – keep cats indoors or let them be outdoors on a tether or leash or kept in an outdoor run. These outdoor runs, often called catios, are easy to build (an online search will yield hundreds of plans) represent a win-win situation because they protect wildlife while still giving the cats the opportunity to enjoy being outside.

Let’s hope that the citizens of Red Deer gave informed feedback on the issue of roaming cats, and that bylaws will be updated to both protect biodiversity and respect cats and cat owners. For more information on this issue, some good websites to start with are https://abcbirds.org/program/cats-indoors/cats-and-birds/ , http://www.ace-eco.org/vol8/iss2/art3/#estimated and https://catsandbirds.ca/

January - 2021 - Canada Jay Update

Four years ago, I wrote a column about the Gray Jay, a bird that had received a lot of recent publicity because the Royal Canadian Geographic Society—after a two-year, country-wide search—announced that Canadians had chosen the Gray Jay as our national bird. In a widely publicized contest, the Gray Jay was chosen over Black-capped Chickadee, Common Loon, Canada Goose and Snowy Owl.

A team of ornithologists (who called themselves Team Canada Jay) then set about getting the name of this species changed from Gray Jay to Canada Jay, a name it held until the American Ornithologists’ Union lumped it with the Oregon Jay and renamed them both Gray Jay in 1957. The campaign was successful, with the American Ornithological Society (which the AOU is now called) restoring the species’s official common name in 2018.

The next hurdle for Team Canada Jay was to get the federal government to ratify the naming in parliament. Sadly, this has not yet happened, much to the frustration of the team as well as many Canadians. A total of 106 of the world’s 195 countries have official birds. Our country has many national symbols, including a national horse. But, alas, no official bird!

The team has written a promotional book entitled “The Canada Jay as Canada’s National Bird” that will be mailed to federal politicians in March. They will also be launching a web site to accompany the book’s release. Senator Diane Griffin is going to put forth a motion on this matter to the Senate after the book’s release, with much fanfare and media attention.

A team of ornithologists (who called themselves Team Canada Jay) then set about getting the name of this species changed from Gray Jay to Canada Jay, a name it held until the American Ornithologists’ Union lumped it with the Oregon Jay and renamed them both Gray Jay in 1957. The campaign was successful, with the American Ornithological Society (which the AOU is now called) restoring the species’s official common name in 2018.

The next hurdle for Team Canada Jay was to get the federal government to ratify the naming in parliament. Sadly, this has not yet happened, much to the frustration of the team as well as many Canadians. A total of 106 of the world’s 195 countries have official birds. Our country has many national symbols, including a national horse. But, alas, no official bird!

The team has written a promotional book entitled “The Canada Jay as Canada’s National Bird” that will be mailed to federal politicians in March. They will also be launching a web site to accompany the book’s release. Senator Diane Griffin is going to put forth a motion on this matter to the Senate after the book’s release, with much fanfare and media attention.

In an attempt to push parliament to act, Team Canada Jay is asking Canadians to sign this petition: https://www.change.org/Repatriate_the_Canada_Jay. The team is hopeful that the federal government will finally ratify the naming and announce the official designation by next Canada Day, July 1, 2021.

While Canada Jays don’t nest in the City of Red Deer, they are common within a half-hour’s drive north and west. And most people who have camped, hiked or skied in the west country or mountains have experienced the delight of being accosted by these intrepid beggars. It is truly a quintessential Canadian Bird.

Let’s hope that Canada will soon have our own official bird—the Canada Jay!

While Canada Jays don’t nest in the City of Red Deer, they are common within a half-hour’s drive north and west. And most people who have camped, hiked or skied in the west country or mountains have experienced the delight of being accosted by these intrepid beggars. It is truly a quintessential Canadian Bird.

Let’s hope that Canada will soon have our own official bird—the Canada Jay!