December 2022 - Ruffed Grouse

I poured myself a second cup of coffee one morning last week, I peered out the kitchen window into the frigid, steel-gray dawn. I was checking the thermometer, which registered a chilly -27 C, when a movement suddenly caught my eye. Squinting, I finally made out the form of a Ruffed Grouse on our cotoneaster shrub, gulping berries while balancing awkwardly on its pencil-thin branches. We are delighted to have Ruffed Grouse sharing our yard with us this winter. We usually see only one at a time, but a couple of weeks ago we observed two individuals feeding on spilled birdseed. It has been interesting to watch them at various times of the day: resting high up in the laurel leaf willows, marching across the yard, skulking low around under the bird feeders, and picking at the remaining cotoneaster berries.

On that frigid morning, I implored the grouse to stay until there was enough light for pictures. But, well before morning had broken, I – not wanting to miss a photo opportunity - slowly opened the window. The grouse, by now at eye-level, stared quizzically at me for a few delightful moments. Just as it turned its attention back to eating, it lost its balance and slid unceremoniously down through the branches and thumped to the ground. Nonplussed, it shook itself off and scampered away under the deck. The poor light resulted in less than stellar images, but it was a memorable encounter. Later that afternoon, it returned for more berries, but this time circled the shrub while peering upward. On three occasions, it suddenly leapt into the air, deftly plucking a berry off a low-hanging branch.

Our yard provides good winter habitat for these grouse, which need protective cover and adequate food sources close to where they can rest/sun themselves during the day and roost at night. Grouse typically eat only two times a day during the winter, and their favourite food is the male bud of the aspen poplar tree. They will also eat other vegetation, including berries and the buds of other tree species. Although the birds usually feed quickly, filling their crops without having to move around very much, I observed and photographed one individual, several years ago, moving slowly along the forest floor, feeding on the dainty green leaves of common pink wintergreen.

During stretches of bitterly cold weather, Ruffed Grouse will plunge down into the snowpack to sleep and roost. They will emerge in the late afternoon to feed before returning to their snug abodes. Their distinctive droppings accumulate in piles, which can be observed after the snowpack melts in the spring.

Most Ruffed Grouse are quite tame, so they provide excellent subjects for wildlife observation and photography. If you encounter one, approach it quietly and take the time to observe its subtle and delicate beauty.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

On that frigid morning, I implored the grouse to stay until there was enough light for pictures. But, well before morning had broken, I – not wanting to miss a photo opportunity - slowly opened the window. The grouse, by now at eye-level, stared quizzically at me for a few delightful moments. Just as it turned its attention back to eating, it lost its balance and slid unceremoniously down through the branches and thumped to the ground. Nonplussed, it shook itself off and scampered away under the deck. The poor light resulted in less than stellar images, but it was a memorable encounter. Later that afternoon, it returned for more berries, but this time circled the shrub while peering upward. On three occasions, it suddenly leapt into the air, deftly plucking a berry off a low-hanging branch.

Our yard provides good winter habitat for these grouse, which need protective cover and adequate food sources close to where they can rest/sun themselves during the day and roost at night. Grouse typically eat only two times a day during the winter, and their favourite food is the male bud of the aspen poplar tree. They will also eat other vegetation, including berries and the buds of other tree species. Although the birds usually feed quickly, filling their crops without having to move around very much, I observed and photographed one individual, several years ago, moving slowly along the forest floor, feeding on the dainty green leaves of common pink wintergreen.

During stretches of bitterly cold weather, Ruffed Grouse will plunge down into the snowpack to sleep and roost. They will emerge in the late afternoon to feed before returning to their snug abodes. Their distinctive droppings accumulate in piles, which can be observed after the snowpack melts in the spring.

Most Ruffed Grouse are quite tame, so they provide excellent subjects for wildlife observation and photography. If you encounter one, approach it quietly and take the time to observe its subtle and delicate beauty.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

November 2022 - Red-breasted Nuthatches

For the past two years, I have greatly enjoying being the Resident Naturalist for Chin Ridge Seeds, a family-owned bird seed company based in Taber, AB. Lucky for me, I get to observe, study, photograph and write about bird feeding and feeder birds!

My most recent assignment was to conduct some field trials on a special bird seed blend and some new products that the company is testing. Armed with my new Go Pro to film the action, I was able to enjoy some time at our little cabin in the woods last week, observing and photographing the activities at the many bird feeding stations in the area.

At this time of year, my Sylvan Lake feeders are visited by Black-capped Chickadees, White-breasted Nuthatches, House Finches, Blue Jays, and Downy, Hairy and Pileated Woodpeckers. The cabin property, which is located in the boreal forest and adjacent to a large larch wetland, attracts additional species, including Canada Jays, Boreal Chickadees, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Brown Creepers, and Dark-eyed Juncos. It is always a treat to see and observe these less-familiar species.

It was the Red-breasted Nuthatches that intrigued me the most on this recent visit. They aren’t rare feeder birds but tend to show up at feeders on a more random basis. They did appear at my Sylvan Lake feeders this summer, which is the first time I’ve ever seen them here. Over the past few years, there have been an increasing number of reports of them using nestboxes, so it is likely that their population is growing and expanding.

Easily identified by their small size and distinctive red/blue/black plumage, these diminutive denizens of the coniferous forests travel with other small passerines but tend to spend most of their time on tree trunks and branches, searching the bark fissures for hidden insects. They often fly up into a tree, then move down the trunk, head-first. While they will occasionally patronize bird feeding stations during the summer, their diet consists mostly of insects that they glean in the forests. However, during the fall and winter, they switch their diet to conifer seeds (including, apparently, seeds that they cached earlier in the season) and will visit feeding stations that offer sunflower seeds, peanuts and suet. As their name implies, they love to “hack” at their food, often hauling away large seeds or chunks of suet which they then wedge into a bark fissure and hammer into bite-sized pieces.

The cabin pair are exceptionally tame, so I was able to enjoy some very close encounters. Despite their small size, I observed that they are aggressive. I watched them chase off chickadees as well as their larger cousins, White-breasted Nuthatches, and even Downy Woodpeckers. On several occasions, I observed the male swoop into the feeder and chase off the female.

Winter arrived suddenly this month, so I encourage everyone to set out a bird feeding station or two. Not only will this supplemental food help some of our avian neighours survive the long winter ahead, watching wild birds is a wonderful way to lift our spirits and feel connected with nature.

My most recent assignment was to conduct some field trials on a special bird seed blend and some new products that the company is testing. Armed with my new Go Pro to film the action, I was able to enjoy some time at our little cabin in the woods last week, observing and photographing the activities at the many bird feeding stations in the area.

At this time of year, my Sylvan Lake feeders are visited by Black-capped Chickadees, White-breasted Nuthatches, House Finches, Blue Jays, and Downy, Hairy and Pileated Woodpeckers. The cabin property, which is located in the boreal forest and adjacent to a large larch wetland, attracts additional species, including Canada Jays, Boreal Chickadees, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Brown Creepers, and Dark-eyed Juncos. It is always a treat to see and observe these less-familiar species.

It was the Red-breasted Nuthatches that intrigued me the most on this recent visit. They aren’t rare feeder birds but tend to show up at feeders on a more random basis. They did appear at my Sylvan Lake feeders this summer, which is the first time I’ve ever seen them here. Over the past few years, there have been an increasing number of reports of them using nestboxes, so it is likely that their population is growing and expanding.

Easily identified by their small size and distinctive red/blue/black plumage, these diminutive denizens of the coniferous forests travel with other small passerines but tend to spend most of their time on tree trunks and branches, searching the bark fissures for hidden insects. They often fly up into a tree, then move down the trunk, head-first. While they will occasionally patronize bird feeding stations during the summer, their diet consists mostly of insects that they glean in the forests. However, during the fall and winter, they switch their diet to conifer seeds (including, apparently, seeds that they cached earlier in the season) and will visit feeding stations that offer sunflower seeds, peanuts and suet. As their name implies, they love to “hack” at their food, often hauling away large seeds or chunks of suet which they then wedge into a bark fissure and hammer into bite-sized pieces.

The cabin pair are exceptionally tame, so I was able to enjoy some very close encounters. Despite their small size, I observed that they are aggressive. I watched them chase off chickadees as well as their larger cousins, White-breasted Nuthatches, and even Downy Woodpeckers. On several occasions, I observed the male swoop into the feeder and chase off the female.

Winter arrived suddenly this month, so I encourage everyone to set out a bird feeding station or two. Not only will this supplemental food help some of our avian neighours survive the long winter ahead, watching wild birds is a wonderful way to lift our spirits and feel connected with nature.

August 2022 - Enjoying Black Terns

Black Terns are beautiful and fascinating water birds. They grace small to medium-sized shallow wetlands, preferring shallow marshes and lakes to large, deep water bodies.

Black terns are easy to identify, as both males and females in breeding plumage are dark gray with jet black heads. They enter their molt fairly early in the season, so at this time of year, adults can range in colour from black to various combinations of black, gray and white. Juveniles are easily identified by their brown scaled upperparts and white heads set off with dusky-colored crowns and ear patches.

Black Terns are also easy to find, even from a vehicle. Just drive slowly by any small pond or slough and you will see them flying gracefully over the water. They can be seen feeding on the wing, but they will also drop down to snatch insects and small fish. If they are nesting, they will vigorously defend their nesting areas by vocalizing and even diving at perceived predators. I have been dive-bombed countless times!

Black Terns are very social birds, often nesting together in loose colonies. They have been observed performing courtship flights, with up to 300 individuals participating. If a pair arrives on the breeding ground already pair-bonded, they may substitute the courtship flight with courtship feeding and various other courtship activities.

The male and female choose nesting sites together, in shallow, sheltered waters where there is abundant emergent vegetation. Their nests, which are shallow mounds, are often placed atop floating dead vegetation. They lay two eggs, which are incubated for about 21 days. The young, which are covered in cinnamon to gray down but have white eye patches, are on the nest for 18 to 21 days. Eyes open, able to lift head and vocalize soon after hatching.

Changing water levels often cause nest failures, which is what appears to have happened to terns (and other waterfowl) this season. We found newly hatched young on a recent kayak trip to Buffalo Lake, and observed many pairs carrying food into the dense bullrush beds, feeding young. Their nests were likely flooded out and they have built second nests.

Sadly, it appears that Black Tern numbers are declining. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, populations declined by 51% between 1966 and 2015. The North American Waterbird Conservation Plan estimates a population of 100,000–500,000 breeding birds in North America. The species is difficult to monitor, as changing water levels often force nesting Black Terns to relocate from year to year or even during a single nesting season. The causes of population declines are not well understood but include drainage or conversion of wetlands and reduction of insect populations by agricultural pesticide use or other contributors to poor water quality. In Central American wintering areas, Black Terns may have been affected by sharp declines in prey species, especially small fish.

Black terns are easy to identify, as both males and females in breeding plumage are dark gray with jet black heads. They enter their molt fairly early in the season, so at this time of year, adults can range in colour from black to various combinations of black, gray and white. Juveniles are easily identified by their brown scaled upperparts and white heads set off with dusky-colored crowns and ear patches.

Black Terns are also easy to find, even from a vehicle. Just drive slowly by any small pond or slough and you will see them flying gracefully over the water. They can be seen feeding on the wing, but they will also drop down to snatch insects and small fish. If they are nesting, they will vigorously defend their nesting areas by vocalizing and even diving at perceived predators. I have been dive-bombed countless times!

Black Terns are very social birds, often nesting together in loose colonies. They have been observed performing courtship flights, with up to 300 individuals participating. If a pair arrives on the breeding ground already pair-bonded, they may substitute the courtship flight with courtship feeding and various other courtship activities.

The male and female choose nesting sites together, in shallow, sheltered waters where there is abundant emergent vegetation. Their nests, which are shallow mounds, are often placed atop floating dead vegetation. They lay two eggs, which are incubated for about 21 days. The young, which are covered in cinnamon to gray down but have white eye patches, are on the nest for 18 to 21 days. Eyes open, able to lift head and vocalize soon after hatching.

Changing water levels often cause nest failures, which is what appears to have happened to terns (and other waterfowl) this season. We found newly hatched young on a recent kayak trip to Buffalo Lake, and observed many pairs carrying food into the dense bullrush beds, feeding young. Their nests were likely flooded out and they have built second nests.

Sadly, it appears that Black Tern numbers are declining. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, populations declined by 51% between 1966 and 2015. The North American Waterbird Conservation Plan estimates a population of 100,000–500,000 breeding birds in North America. The species is difficult to monitor, as changing water levels often force nesting Black Terns to relocate from year to year or even during a single nesting season. The causes of population declines are not well understood but include drainage or conversion of wetlands and reduction of insect populations by agricultural pesticide use or other contributors to poor water quality. In Central American wintering areas, Black Terns may have been affected by sharp declines in prey species, especially small fish.

July 2022 - "Black Gopher" Encounter

I first learned about “black gophers” over 30 years ago, when fellow naturalists reported seeing them each spring in a pasture near Morningside. Unfortunately, I never got to see that small population before it disappeared.

When a friend, who lives north of Ponoka, contacted me a few weeks ago to say that she was surprised to see several young black Richardson’s Ground Squirrels in her pasture, I quickly changed my day’s plans and went over to see them. I wasn’t disappointed!

In a field teeming with newly emerged young ground squirrels, we counted at least six black individuals. Although it was difficult to determine family units because they were busy scurrying about, disappearing and reappearing at various entrance holes, we concluded that the black individuals had normal-colored siblings.

As I approached the pasture, the youngsters heeded the warning whistles of a sentinel adult and scurried down their holes to safety. Fortunately, two little black ones seemed to be quite curious and tame. I walked slowly in their direction, then dropped down and belly crawled to within touching distance. For a magical half hour, we played a gopher version of peek-a-boo.

These black individuals were melanistic, displaying a genetic mutation that causes an abnormal increase in the production of melanin. Melanistic individuals are entirely black; they even have black eyes!

Melanism occurs throughout the animal kingdom and, among Alberta mammals, is most commonly observed among Eastern Gray Squirrels. A small number of Eastern Gray Squirrels were released from the Calgary Zoo some decades ago and are now common in Calgary as well as a few other surrounding towns.

It is not known how common black morph RIchardson's Ground Squirrels are in Alberta. After posting my observation of the Ponoka morphs on social media, I received reports of other observations across the province. I also received reports that landowners who control the ground squirrel population on their farms will often spare the black individuals, thus increasing local numbers.

Based on the short time I spent with this population, the black individuals seemed to stand out more distinctively in the green pasture than their brown counterparts. But closer observation would be needed to determine if they are more vulnerable to depredation.

While on the topic of “gophers,” I’d like to reiterate that Richardson’s Ground Squirrels can cause issues for farmers when their numbers are high, but it is important to note that they play a vital role in sustaining healthy ecosystems. Not only do these small mammals provide sustenance for birds of prey and other predators, their tunneling churns the soil and their burrows provide homes for a variety of other species.

I’d be interested in receiving any other locations and/or observations of black morph Richardson’s Ground Squirrels in Central Alberta.

When a friend, who lives north of Ponoka, contacted me a few weeks ago to say that she was surprised to see several young black Richardson’s Ground Squirrels in her pasture, I quickly changed my day’s plans and went over to see them. I wasn’t disappointed!

In a field teeming with newly emerged young ground squirrels, we counted at least six black individuals. Although it was difficult to determine family units because they were busy scurrying about, disappearing and reappearing at various entrance holes, we concluded that the black individuals had normal-colored siblings.

As I approached the pasture, the youngsters heeded the warning whistles of a sentinel adult and scurried down their holes to safety. Fortunately, two little black ones seemed to be quite curious and tame. I walked slowly in their direction, then dropped down and belly crawled to within touching distance. For a magical half hour, we played a gopher version of peek-a-boo.

These black individuals were melanistic, displaying a genetic mutation that causes an abnormal increase in the production of melanin. Melanistic individuals are entirely black; they even have black eyes!

Melanism occurs throughout the animal kingdom and, among Alberta mammals, is most commonly observed among Eastern Gray Squirrels. A small number of Eastern Gray Squirrels were released from the Calgary Zoo some decades ago and are now common in Calgary as well as a few other surrounding towns.

It is not known how common black morph RIchardson's Ground Squirrels are in Alberta. After posting my observation of the Ponoka morphs on social media, I received reports of other observations across the province. I also received reports that landowners who control the ground squirrel population on their farms will often spare the black individuals, thus increasing local numbers.

Based on the short time I spent with this population, the black individuals seemed to stand out more distinctively in the green pasture than their brown counterparts. But closer observation would be needed to determine if they are more vulnerable to depredation.

While on the topic of “gophers,” I’d like to reiterate that Richardson’s Ground Squirrels can cause issues for farmers when their numbers are high, but it is important to note that they play a vital role in sustaining healthy ecosystems. Not only do these small mammals provide sustenance for birds of prey and other predators, their tunneling churns the soil and their burrows provide homes for a variety of other species.

I’d be interested in receiving any other locations and/or observations of black morph Richardson’s Ground Squirrels in Central Alberta.

June 2022 - American Dipper

American Dippers are nondescript, chunky gray birds that hold the distinction of being North America’s only aquatic passerine. Anyone who visits the west country has likely seen them as they splash about in the water.

We discovered a nest last summer in the Crowsnest Pass, which was an exciting find! We returned to the same stream last week and were pleased to find the nest being reused. In addition to watching and photographing the adult dippers, we were able to hear both the male and female sing—a raucous and surprisingly loud series of notes that easily carried over the roar of the river.

So-named because of their habit of “dipping,” American Dippers are found around noisy, fast-moving, clear and unpolluted streams that have certain attributes: waterfalls and pools for feeding; rocks and fallen trees for shelter and roosting; and near-by rock faces with overhanging ledges for nest sites. Some birds remain year-round in the same area while those that breed in the high mountains may migrate down to lower elevations for the winter.

American Dippers are well adapted for their frigid lifestyle—a low metabolic rate, blood with extra oxygen-carrying capacity, legs with a special counter-flow artery/vein system, down feathers next to their skin, and a thick coat of feathers. Narrow white feathers grow on their upper and lower eyelids to help insulate their eyes from cold water.

While they will often glean terrestrial insects, even by probing into leaf litter and turning over stones, most foraging entails some sort of plunging to access the aquatic larvae of caddisflies, mayflies etc. They will plunge while wading, swimming, diving and even flying.

An American Dipper nest is truly a work of art! Crafted mostly by the female, it is a two-part ball-like structure with a small, water-facing and often canopy-covered entrance hole. The outer shell, which is attached to a rock wall, is constructed of moss interwoven with grass stems and roots while the inner chamber is a cup or pad woven from grass, leaves and bark.

The female lays, then solely incubates, a clutch of four to five eggs for about two weeks. The nestlings remain in the nest for about a month but, before fledging, will creep out of the nest to explore the nearby nest ledge. Once fledged, they quickly learn adult skills but may beg to be fed by their parents for a month or more. Juveniles eventually disperse, often crossing over drainage divides to other streams.

Fascinatingly, soon after their young fledge, the parents remove the inner nest lining and toss it in the stream below, likely to deter predators and/or prevent blowfly infestations.

If you have the privilege of observing American Dippers this summer, take the time to appreciate the grace, beauty and remarkable abilities of these fascinating birds!

We discovered a nest last summer in the Crowsnest Pass, which was an exciting find! We returned to the same stream last week and were pleased to find the nest being reused. In addition to watching and photographing the adult dippers, we were able to hear both the male and female sing—a raucous and surprisingly loud series of notes that easily carried over the roar of the river.

So-named because of their habit of “dipping,” American Dippers are found around noisy, fast-moving, clear and unpolluted streams that have certain attributes: waterfalls and pools for feeding; rocks and fallen trees for shelter and roosting; and near-by rock faces with overhanging ledges for nest sites. Some birds remain year-round in the same area while those that breed in the high mountains may migrate down to lower elevations for the winter.

American Dippers are well adapted for their frigid lifestyle—a low metabolic rate, blood with extra oxygen-carrying capacity, legs with a special counter-flow artery/vein system, down feathers next to their skin, and a thick coat of feathers. Narrow white feathers grow on their upper and lower eyelids to help insulate their eyes from cold water.

While they will often glean terrestrial insects, even by probing into leaf litter and turning over stones, most foraging entails some sort of plunging to access the aquatic larvae of caddisflies, mayflies etc. They will plunge while wading, swimming, diving and even flying.

An American Dipper nest is truly a work of art! Crafted mostly by the female, it is a two-part ball-like structure with a small, water-facing and often canopy-covered entrance hole. The outer shell, which is attached to a rock wall, is constructed of moss interwoven with grass stems and roots while the inner chamber is a cup or pad woven from grass, leaves and bark.

The female lays, then solely incubates, a clutch of four to five eggs for about two weeks. The nestlings remain in the nest for about a month but, before fledging, will creep out of the nest to explore the nearby nest ledge. Once fledged, they quickly learn adult skills but may beg to be fed by their parents for a month or more. Juveniles eventually disperse, often crossing over drainage divides to other streams.

Fascinatingly, soon after their young fledge, the parents remove the inner nest lining and toss it in the stream below, likely to deter predators and/or prevent blowfly infestations.

If you have the privilege of observing American Dippers this summer, take the time to appreciate the grace, beauty and remarkable abilities of these fascinating birds!

May 2022 - Avian Flu

As the Resident Naturalist for Mother Nature’s birdseed, I have been tasked with keeping updated about the avian flu. The burning question for backyard bird feeding enthusiasts is “do I or do I not take down my feeders?” I hope this column can help answer that question.

The H5N1 subtype of avian Influenza virus is spreading in Canada, causing severe illness and mortality in domestic poultry flocks. It has been detected in waterfowl and birds of prey but is NOT currently considered a disease threat to songbirds, including species that frequent backyard feeders.

As of May 24th, Environment and Climate Change Canada advises that the use of bird feeders is still safe on properties without domestic poultry. All major organizations that are recognized authorities on birds (e.g., Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, the American Bird Conservancy and Birds Canada) are not recommending that bird feeders, except those on poultry farms, be taken down.

To Minimize Risk:

1. Prevent over-crowding at feeding stations: With the exception of Pine Siskins, which have not yet appeared in large numbers, the only other common flocking species at this time of year are non-native House Sparrows. To encourage resident House Sparrows to disperse, avoid offering mixes that contain millet, corn and milo. Instead, offer suet mixtures, peanut butter mixtures, and/or sunflower chips from tube feeders that have small portals. Even better use House Sparrow-proof upside down tube feeders.

Wide spacing of feeders is also recommended, as spaced feeders will enable the less dominant birds to feed (reducing their wait times at crowded feeders, thus resulting in fewer concentrated droppings) and will result in fewer birds at each feeder. If possible, move the feeders to new locations each week.

2. Sanitation: Diseases spread between birds through direct contact and via contaminated feces and saliva. Replacing tray feeders with tube and hopper feeders will reduce the risk of birds contacting each other and will prevent fecal contamination.

It is also important to keep feeding stations clean by washing them (including the perches) once a week with hot soapy water and/or a diluted bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water). Air dry them before adding more seed.

In addition to moving feeders frequently, cleaning the area under feeding stations is also important. While many ground-feeding birds, especially migrating native sparrows, prefer to feed on the ground, it is important to rake up the litter that has accumulated over the winter. To minimize the mess, serve sunflower chips and “no mess” mixes containing only shelled seeds. Hummingbird feeders and other offerings, including commercial suet blocks, grape jelly/orange halves can also be set out.

· If you observe sick or dead birds. There is little you can do to help a bird once it has become ill. If feasible, stay with the bird so it doesn’t disappear and call Medicine River Wildlife Centre (403-728-3467). Wildlife rehabbers follow strict protocols issued by the Canadian Wildlife Service. If a cat happens to be stalking the sick bird, chase the cat away or put it indoors (cats are serious bird predators so should never be allowed outside anyway!).

Never touch a sick bird with your bare hands. If the bird has died, use rubber gloves to place it in a plastic bag. Place it in a second bag and dispose of it with household garbage. If the ill/dead birds are waterfowl or birds of prey, call Alberta Environment and Parks at 310-0000. Sick and dead birds can also be reported to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative information line at 1-800-567-2033 or by using their online reporting tool.

· Be proactive! The most significant contribution that individual landowners can make to supporting and conserving native birds and other wildlife is to provide habitat. High quality habitat (space within which wild creatures can find food, water and shelter) can be offered, even in small yards and gardens. For more details, check out my book: NatureScape Alberta: Creating and Caring for Wildlife Habitat at Home. Now is the perfect time to plan and start transforming your yard into a safe and healthy haven for our wild neighbours!

Websites for updated avian flu information:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/avian-influenza-outbreak-should-you-take-down-your-bird-feeders/

https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/migratory-game-bird-hunting/avian-influenza-wild-birds.html

The H5N1 subtype of avian Influenza virus is spreading in Canada, causing severe illness and mortality in domestic poultry flocks. It has been detected in waterfowl and birds of prey but is NOT currently considered a disease threat to songbirds, including species that frequent backyard feeders.

As of May 24th, Environment and Climate Change Canada advises that the use of bird feeders is still safe on properties without domestic poultry. All major organizations that are recognized authorities on birds (e.g., Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, the American Bird Conservancy and Birds Canada) are not recommending that bird feeders, except those on poultry farms, be taken down.

To Minimize Risk:

1. Prevent over-crowding at feeding stations: With the exception of Pine Siskins, which have not yet appeared in large numbers, the only other common flocking species at this time of year are non-native House Sparrows. To encourage resident House Sparrows to disperse, avoid offering mixes that contain millet, corn and milo. Instead, offer suet mixtures, peanut butter mixtures, and/or sunflower chips from tube feeders that have small portals. Even better use House Sparrow-proof upside down tube feeders.

Wide spacing of feeders is also recommended, as spaced feeders will enable the less dominant birds to feed (reducing their wait times at crowded feeders, thus resulting in fewer concentrated droppings) and will result in fewer birds at each feeder. If possible, move the feeders to new locations each week.

2. Sanitation: Diseases spread between birds through direct contact and via contaminated feces and saliva. Replacing tray feeders with tube and hopper feeders will reduce the risk of birds contacting each other and will prevent fecal contamination.

It is also important to keep feeding stations clean by washing them (including the perches) once a week with hot soapy water and/or a diluted bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water). Air dry them before adding more seed.

In addition to moving feeders frequently, cleaning the area under feeding stations is also important. While many ground-feeding birds, especially migrating native sparrows, prefer to feed on the ground, it is important to rake up the litter that has accumulated over the winter. To minimize the mess, serve sunflower chips and “no mess” mixes containing only shelled seeds. Hummingbird feeders and other offerings, including commercial suet blocks, grape jelly/orange halves can also be set out.

· If you observe sick or dead birds. There is little you can do to help a bird once it has become ill. If feasible, stay with the bird so it doesn’t disappear and call Medicine River Wildlife Centre (403-728-3467). Wildlife rehabbers follow strict protocols issued by the Canadian Wildlife Service. If a cat happens to be stalking the sick bird, chase the cat away or put it indoors (cats are serious bird predators so should never be allowed outside anyway!).

Never touch a sick bird with your bare hands. If the bird has died, use rubber gloves to place it in a plastic bag. Place it in a second bag and dispose of it with household garbage. If the ill/dead birds are waterfowl or birds of prey, call Alberta Environment and Parks at 310-0000. Sick and dead birds can also be reported to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative information line at 1-800-567-2033 or by using their online reporting tool.

· Be proactive! The most significant contribution that individual landowners can make to supporting and conserving native birds and other wildlife is to provide habitat. High quality habitat (space within which wild creatures can find food, water and shelter) can be offered, even in small yards and gardens. For more details, check out my book: NatureScape Alberta: Creating and Caring for Wildlife Habitat at Home. Now is the perfect time to plan and start transforming your yard into a safe and healthy haven for our wild neighbours!

Websites for updated avian flu information:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/avian-influenza-outbreak-should-you-take-down-your-bird-feeders/

https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/migratory-game-bird-hunting/avian-influenza-wild-birds.html

April 2022 - Long-tailed Weasel

I have had the recent good fortune to spend some quality time observing and photographing a Long-tailed Weasel. This weasel, named “Nod” by his human neighours, has been hanging around a residence south of Calgary. When I first photographed Nod on March 24, he was still snow white. On my last visit, April 21, he looked like a completely different creature.

We have been privileged to watch Nod undergo one of two annual moults; in April and May, Long-tailed Weasels (and their cousins, Short-tailed Weasels and Least Weasels) transform from their winter white pelage into a two-toned brown/tawny colour. In October and November, they moult back to pure white. Each moult takes three to four weeks, with mismatches often occurring between pelage colour and the surrounding landscape. Since snow had long melted in the Calgary area by mid-April, Nod’s motley white and brown coat revealed him as a frenetic little beacon zipping around against the still-brown grass.

A ferocious and active predator that hunts by scent and prefers to eat fresh prey, the Long-tailed Weasel feeds primarily on small rodents but has been known to tackle mammals as large as hares. Other prey includes small birds, bird eggs, reptiles, amphibians, fish, earthworms, insects and even bats.

Long-tailed Weasels mate in July and August, but the implantation of the fertilized egg onto the uterine wall is delayed until March. Although the gestation period lasts 10 months, embryonic development takes place only during the last four weeks. This timing results in the young being born in April and May, when small rodents are most abundant.

It has been an interesting experience watching Nod because his hunting schedule follows no set pattern. Some days he is a no-show; other days, he entertains by being visible and active for hours at a time. Before observing Nod, who often scurries up tall trees, I was not aware that weasels are as adept at climbing trees as they are exploring underground.

During the winter, Nod caught voles and mice, but by mid-April he turned more of his attention to exploring the many ground squirrel and pocket gopher dens in the area. Most recently, he has taken a keen interest in a large woodpile and seems to be using a nestbox for occasional naps. Who knows if he will continue to call this area home, or if he will move on to other environs? It has been a rare and wonderful treat to have had the opportunity to be in his company!

We have been privileged to watch Nod undergo one of two annual moults; in April and May, Long-tailed Weasels (and their cousins, Short-tailed Weasels and Least Weasels) transform from their winter white pelage into a two-toned brown/tawny colour. In October and November, they moult back to pure white. Each moult takes three to four weeks, with mismatches often occurring between pelage colour and the surrounding landscape. Since snow had long melted in the Calgary area by mid-April, Nod’s motley white and brown coat revealed him as a frenetic little beacon zipping around against the still-brown grass.

A ferocious and active predator that hunts by scent and prefers to eat fresh prey, the Long-tailed Weasel feeds primarily on small rodents but has been known to tackle mammals as large as hares. Other prey includes small birds, bird eggs, reptiles, amphibians, fish, earthworms, insects and even bats.

Long-tailed Weasels mate in July and August, but the implantation of the fertilized egg onto the uterine wall is delayed until March. Although the gestation period lasts 10 months, embryonic development takes place only during the last four weeks. This timing results in the young being born in April and May, when small rodents are most abundant.

It has been an interesting experience watching Nod because his hunting schedule follows no set pattern. Some days he is a no-show; other days, he entertains by being visible and active for hours at a time. Before observing Nod, who often scurries up tall trees, I was not aware that weasels are as adept at climbing trees as they are exploring underground.

During the winter, Nod caught voles and mice, but by mid-April he turned more of his attention to exploring the many ground squirrel and pocket gopher dens in the area. Most recently, he has taken a keen interest in a large woodpile and seems to be using a nestbox for occasional naps. Who knows if he will continue to call this area home, or if he will move on to other environs? It has been a rare and wonderful treat to have had the opportunity to be in his company!

March 2022 - Celebrating Purple Martins

My interest in Purple Martins was kindled back in the 1980s when our father bought a house from a friend. The box was a work of art, but – like many well-intentioned but poorly designed boxes from that era – it was constructed from thin plywood, couldn’t be opened, and had to be affixed to the top of a tall pole. Since it couldn’t be accessed and our farm was overrun with House Sparrows, the house soon became a sparrow slum. Within a couple years it deteriorated and was taken down.

During the early 1990s, an elderly friend volunteered to install a Purple Martin house at my Sylvan Lake acreage as well as two houses at Ellis Bird Farm (EBF). Although these houses better designed, the set-up was still problematic because the boxes couldn’t be easily monitored during the breeding season. However, they attracted a few pairs of martins.

It was wonderful to see these birds return after long absence. Charlie and Winnie Ellis, founders of EBF, had at thriving colony in their yard during the 1960s and 1970s. Numbers gradually declined over the years, then a severe spring storm in 1982 decimated the colony.

It was in 1998 that the EBF martin program became formally established through the generous mentorship of Del and Debra McKinnon of the Purple Martin Conservancy (PMC). The PMC has perfected a box style that maximize breeding success, including good ventilation, internal cavity and porch dimensions to prevent owl depredation, and overhangs to provide maximum protection from the weather. The martin colony quickly responded to these hours and, as martin numbers increased, additional houses were added.

The PMC-EBF team carefully monitored the boxes over the years, banded both nestlings and adults, and encouraged others to become Purple Martin landlords by developing fact sheets, co-hosting events, and selling houses and kits.

The site was expanded in 2015 when a local martin enthusiast, Jim Boyd, bequeathed an additional three 12-unit houses just before his passing. With this addition, a total of 113 cavities were available and over 100 nesting pairs graced the site.

In 2012, we joined forces with Dr. Kevin Fraser to undertake a Purple Martin migration research program involving the use of light level geolocators. The martins nesting in Central Alberta are at the farthest north limit of their breeding range, so this project provided the first-ever insight into their migration routes and overwintering locations. How exciting it was to welcome the first geo’d bird back in 2013. We named this bird Amelia and the story of her remarkable journey, which can be found on my website (see link below), provided information new to science.

In honour of my retirement, the PMC gifted me a beautiful Purple Martin house to install near my Sylvan Lake home. I look forward to the chatter of these beautiful birds returning to our bay this summer. I am also excited to be involved with a new PMC- led initiative around Sylvan Lake to bolster local populations by setting up and maintaining boxes in various locations around the lake.

During the early 1990s, an elderly friend volunteered to install a Purple Martin house at my Sylvan Lake acreage as well as two houses at Ellis Bird Farm (EBF). Although these houses better designed, the set-up was still problematic because the boxes couldn’t be easily monitored during the breeding season. However, they attracted a few pairs of martins.

It was wonderful to see these birds return after long absence. Charlie and Winnie Ellis, founders of EBF, had at thriving colony in their yard during the 1960s and 1970s. Numbers gradually declined over the years, then a severe spring storm in 1982 decimated the colony.

It was in 1998 that the EBF martin program became formally established through the generous mentorship of Del and Debra McKinnon of the Purple Martin Conservancy (PMC). The PMC has perfected a box style that maximize breeding success, including good ventilation, internal cavity and porch dimensions to prevent owl depredation, and overhangs to provide maximum protection from the weather. The martin colony quickly responded to these hours and, as martin numbers increased, additional houses were added.

The PMC-EBF team carefully monitored the boxes over the years, banded both nestlings and adults, and encouraged others to become Purple Martin landlords by developing fact sheets, co-hosting events, and selling houses and kits.

The site was expanded in 2015 when a local martin enthusiast, Jim Boyd, bequeathed an additional three 12-unit houses just before his passing. With this addition, a total of 113 cavities were available and over 100 nesting pairs graced the site.

In 2012, we joined forces with Dr. Kevin Fraser to undertake a Purple Martin migration research program involving the use of light level geolocators. The martins nesting in Central Alberta are at the farthest north limit of their breeding range, so this project provided the first-ever insight into their migration routes and overwintering locations. How exciting it was to welcome the first geo’d bird back in 2013. We named this bird Amelia and the story of her remarkable journey, which can be found on my website (see link below), provided information new to science.

In honour of my retirement, the PMC gifted me a beautiful Purple Martin house to install near my Sylvan Lake home. I look forward to the chatter of these beautiful birds returning to our bay this summer. I am also excited to be involved with a new PMC- led initiative around Sylvan Lake to bolster local populations by setting up and maintaining boxes in various locations around the lake.

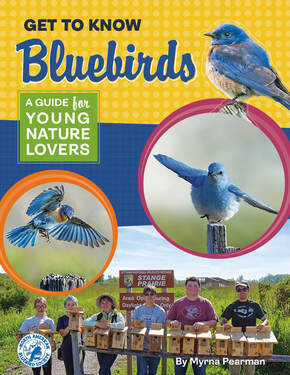

February 2022 - Celebrating Bluebirds

Readers of this column will know that I have spent much of my life watching and studying Mountain Bluebirds. From starting my own small bluebird trail as a young teen on our family farm north of Rimbey to a career dedicated to carrying on the legacy of bluebird legends, Charlie and Winnie Ellis, bluebirds have been near and dear to my heart.

It has been my privilege to share my love of bluebirds in various ways—from collecting data, banding, conducting research and writing scientific articles to writing books and delivering presentations to both children and adults.

In 2002, the Red Deer River Naturalists teamed up with Mountain Bluebird Trails, Montana, (MBT) to publish the Mountain Bluebird Trail Monitoring Guide. A PDF of the book can be downloaded from the RDRN website: https://rdrn.ca/programs/mountain-bluebird-trail-monitoring-guide/. Copies can also be purchased here on my website.

In 2009, I again teamed up MBT to write a bluebird book for children--Children’s Bluebird Activity Book—which can be downloaded as a PDF from the MBT website: http://www.mountainbluebirdtrails.com/Final%20PDF%20of%20the%20book.pdf

In 2020, the North American Bluebird Society (NABS) asked me to write another book about bluebirds, this time for young adults. This book has been recently published and is available as a downloadable PDF from the NABS website: http://www.nabluebirdsociety.org/publications/. This book was challenging because it covers all three species of bluebirds, but it was inspiring to connect with bluebird friends and colleagues from across the continent and to meet bluebird photographers from coast to coast – all of whom were happy to share their beautiful photographs. The plan is to eventually get this book printed.

It is hard to believe that the bluebirds will start showing up in Central Alberta within the next few weeks! If you would like to help bluebirds by setting out boxes or starting a bluebird trail, these books have all the information you need, including plans for nestboxes that work well in this region. Boxes should be set out by the middle of March. Sadly, Mountain Bluebird populations across most of their range were at an all-time low last year. Let’s hope their numbers rebound this season.

It has been my privilege to share my love of bluebirds in various ways—from collecting data, banding, conducting research and writing scientific articles to writing books and delivering presentations to both children and adults.

In 2002, the Red Deer River Naturalists teamed up with Mountain Bluebird Trails, Montana, (MBT) to publish the Mountain Bluebird Trail Monitoring Guide. A PDF of the book can be downloaded from the RDRN website: https://rdrn.ca/programs/mountain-bluebird-trail-monitoring-guide/. Copies can also be purchased here on my website.

In 2009, I again teamed up MBT to write a bluebird book for children--Children’s Bluebird Activity Book—which can be downloaded as a PDF from the MBT website: http://www.mountainbluebirdtrails.com/Final%20PDF%20of%20the%20book.pdf

In 2020, the North American Bluebird Society (NABS) asked me to write another book about bluebirds, this time for young adults. This book has been recently published and is available as a downloadable PDF from the NABS website: http://www.nabluebirdsociety.org/publications/. This book was challenging because it covers all three species of bluebirds, but it was inspiring to connect with bluebird friends and colleagues from across the continent and to meet bluebird photographers from coast to coast – all of whom were happy to share their beautiful photographs. The plan is to eventually get this book printed.

It is hard to believe that the bluebirds will start showing up in Central Alberta within the next few weeks! If you would like to help bluebirds by setting out boxes or starting a bluebird trail, these books have all the information you need, including plans for nestboxes that work well in this region. Boxes should be set out by the middle of March. Sadly, Mountain Bluebird populations across most of their range were at an all-time low last year. Let’s hope their numbers rebound this season.